This classic was able to be both an engaging crowd-pleaser and a subversive commentary.

Steven Spielberg once famously (and controversially) stated that he believed that superhero movies would “go the way of the Western” and gradually become less prominent. Spielberg’s comments aren’t entirely without merit; Westerns have never gone away, but the genre has evolved throughout many eras. Spaghetti westerns didn’t start popping up until the ’60s, neo-Westerns like Brokeback Mountain and Hell or High Water gained prominence in the ’90s, and the Western films of the past two decades have helped to spotlight underrepresented voices and maintain more historical accuracy.

However, few figures in cinematic history have been as instrumental in launching and promoting the Western genre as the legendary John Ford, who Spielberg himself has stated is a heavy influence on his work. Ford’s 1939 Western Stagecoach was one of the first Western films to ever become a blockbuster event, and it served as Ford’s first collaboration with John Wayne. The two would go on to create classic westerns like Fort Apache, 3 Godfathers, Rio Grande, and She Wore A Yellow Ribbon. Their 1956 western The Searchers is often cited as one of the best films ever made, and subverted the clichés of the genre by focusing on an obsessive anti-hero.

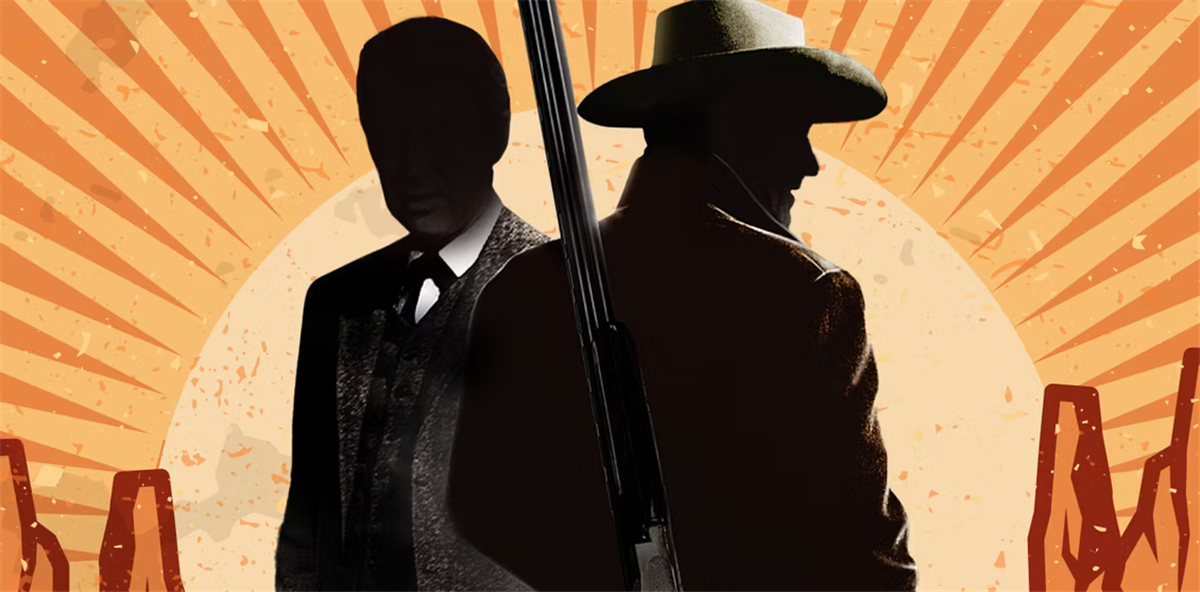

However, the last film that the pair worked on was a film that’s equally insightful in dissecting Western myths. It’s fitting that 1962’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was their last entry in the genre, as it came during the decade when the west itself had moved away from Hollywood. The 1960s were the era of the Spaghetti Western, and the arrival of Sergio Leone and his “Dollars” trilogy announced an exciting new twist that effectively ended Hollywood’s dominance.

‘The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance’ Is About Revising History

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance isn’t quite a “revisionist” Western, although ironically the story itself is about historical revisionism. While it incorporates more political subtext than most of Ford’s other films, the film is still constructed in the classical fashion; Ford even returned to his black-and-white roots. He reflects on the end of the era by honoring its past, incorporating the perspectives of two very different types of Western heroes. 60 years later, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance remains a critical achievement that examines mythology, political participation, and sensitive masculinity.

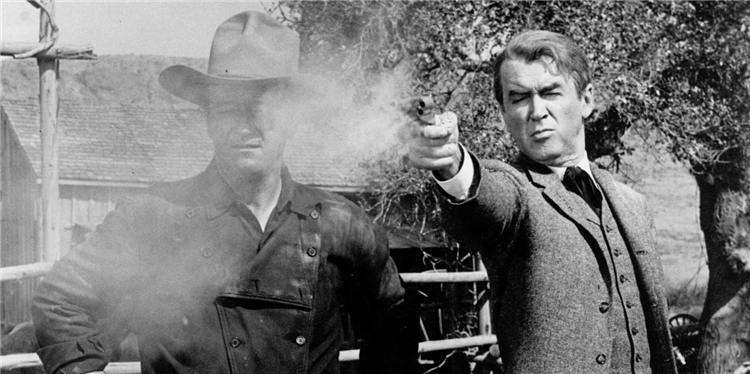

The film opens with a stagecoach journey by Senator Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart) and his wife Hallie (Vera Miles) to the small frontier town of Shinbone. Ransom makes the long trip from the U.S. Capital in order to attend the funeral of a local lawman, Tom Doniphon (Wayne). His arrival is immediately met with confusion by the local villagers. Why would a prominent, highly influential politician go out of his way to honor a common rancher? As the film flashes backward in time, it’s revealed that the two men had a much deeper relationship than anyone realized.

25 years earlier, Ransom was only a young, idealistic lawyer whose urban attitudes made him stick out like a sore thumb on the frontier roads. He’s forced to stay in Shinbone after he’s robbed and severely beaten by the villainous outlaw Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin) and his criminal gang. Ransom is taken in by the small community, and insists that the authorities must bring Valance to justice. The townspeople are skeptical; this is lawless territory, and there’s no way someone as elusive as Valance could be captured by traditional means. This frustrates Ransom, who is determined to bring civilization and legitimacy to the city on the edge of society.

Ransom is introduced to the local gunslinger Tom Domiphon, who takes pity on him for his ignorance. Tom generally dislikes politicians, suggesting that men who sit in offices know nothing that common laborers don’t. However, he surprisingly befriends Ransom, realizing he’s just as adamant about justice as he is. The two men bond over making the community stronger, but Tom begins to realize that Ransom is changing the town for good. It’s here where Ford shows his hand; he’s celebrating a figure like Tom, but indicating that his generation is ending.

Tom and Ransom

Ransom begins helping Shinbone make radical changes to its infrastructure, and the community follows him earnestly. As he sets up his law practice, Ransom establishes the town’s first newspaper, oversees the construction of a schoolhouse, organizes town meetings and hearings, and encourages his fellow inhabitants to consider pushing the federal government for statehood. He empowers the community, as they can participate and allow their voices to be heard. It’s a rallying cry for Ford’s personal projects; despite the fact that he collaborated with someone like Wayne, Ford was a lifelong progressive.

Tom respects that Ransom is getting down in the dirt and connecting the people, and he enjoys working with him to keep people safe. Their friendship is never in doubt, but Tom feels out of place as Shinbone becomes connected to the larger national political structure. There’s something that he always appreciated about being off on the fringes. Ford shows that Tom represents the Western itself; in order to remain relevant, he must be willing to evolve.

However, it’s during the eventual climactic showdown when Valance returns that Ford sets his critical sights on the audience. As someone who knows more about the genre than anyone, Ford has grown to recognize what audiences really want. Ransom is forced to gun down Valance, earning him recognition as a hero that follows him throughout his career.

As we see in the flash forward in time, it was really Tom that killed Valance. Ransom could never bring himself to harm another, even though he knows that’s what people want to hear. This lionization of violence is evident in the film’s haunting closing line; a train conductor remarks to Ransom that “nothing’s too good for the man who shot Liberty Valance.”

All of Ford’s westerns are unique, but The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance was able to be both an engaging crowd-pleaser and a subversive commentary. It’s a melancholy, yet eminently watchable film about the end of an era, and bookends the entire Golden Age of Westerns that Ford himself had essentially created with Stagecoach. It’s rare to see a filmmaker so frank about their achievements, but for Ford, it was all in the text.