The 1974 Michael Cimino adventure is more than just a buddy film.

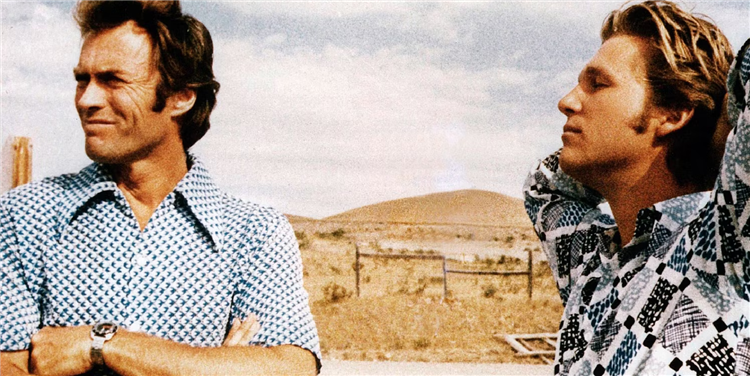

Clint Eastwood, dressed in minister garb, stands at the pulpit of a tiny Idaho church preaching to his small congregation. “And the leopard shall lie down with the kid,” he says to his captive audience. Cut to 24-year-old Jeff Bridges strutting through a weed-covered field dressed in black leather pants, plaid shirt unbuttoned at the top, silver chain dangling over his chest. The strikingly handsome young man looks more suited to Greenwich Village than small town America. Within the first three minutes of Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, writer-director Michael Cimino is already telegraphing to the audience that the relationship between the film’s two male lead characters will be more than just a friendship. The 1974 classic is, in fact, a romantic drama, with elements of action and adventure thrown in as mere framing devices.

The late author and film historian Vitto Russo, in his 1981 book about LGBTQ+ representation in movies, The Celluloid Closet, described the film as a “homophobic ‘buddy’ movie, overflowing with relationships that Hollywood would not allow to be portrayed as same-sex and sexual.” While it’s true that Cimino loaded Thunderbolt and Lightfoot with veiled allusions to homosexuality, that veil is deliberately thin, and looking at the film from a distance of nearly half a century since its release, it’s not difficult to understand the constraints Cimino was likely under in his attempt to tell this unconventional love story. At the same time, the movie remains a rather bold exploration of “bromance,” with an emphasis on the “romance” part.

‘Thunderbolt and Lightfoot’: A Romance Posing As an Action Adventure Film

In many ways, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot follows standard romantic drama conventions, which was probably Cimino’s intention when he crafted the movie’s script for this, his debut feature. The film’s main characters even “meet cute,” as far as career criminal characters go. Eastwood’s Thunderbolt (a nickname he picked up during the Korean War) is running from a man trying to shoot him dead, while Bridges’ Lightfoot (a take on the character possibly being “light in the loafers,” a derogatory phrase once used to describe gay men) has just stolen a car and is on the run. Lightfoot hits Thunderbolt’s would-be assassin with his car, and Thunderbolt hops in and hitches a ride with the young thief. Thunderbolt is also a thief trying to elude two of his former co-conspirators, Red and Eddie (George Kennedy and Geoffrey Lewis), and Lightfoot is a drifter estranged from his family because he was “a little too much for them to handle,” the specific reasons for which are never explored in the film.

Thunderbolt almost immediately comments on his young rescuer’s blue eyes, and Lightfoot is instantly fascinated by the good-looking mature man dressed as a preacher. In a scene that can be described as nothing other than erotic, Lightfoot gazes longingly as Thunderbolt strips off his preacher’s vest and stands bare-chested. Lightfoot is infatuated with the enigmatic lawbreaker, but Thunderbolt initially resists forming any attachment to the kid who saved his life. When Thunderbolt’s pursuers close in on his trail, though, he decides to continue his journey with Lightfoot. “We’re gonna have to stop meeting like this. People are gonna talk,” Lighfoot tells the object of his affection when Thunderbolt hops back into the car. “Believe me, where there’s smoke, there’s fire, ya know,” Lightfoot teases. With that, the two are off to pursue a life of crime and commitment.

The Film’s Female Characters Are on the Periphery

As the two hit the road, they encounter an assortment of lovely ladies along the way, but like many female characters in Cimino’s films (think The Deer Hunter and Heaven’s Gate), those who appear in this movie are on the periphery and serve mainly to remind the audience that even the affections of a beautiful young lass can’t break the bond between the two men. In a particularly telling scene, Lightfoot brings home two women (Catherine Bach and June Fairchild) to party with the men. Thunderbolt seems completely ill-at-ease and out of his element as one of the women attempts to seduce him, as if this kind of intimacy is something completely new to him and certainly not welcome. The ladies exit soon enough, and the focus returns to the two anti-heroes, a reminder from Cimino about where the film’s true relationship is.

The Relationship Between the Two Leads Breeds Anger

Eventually, the two outlaws again meet up with Red and Eddie, and decide to work as a team to pull off a heist of a Montana armored bank vault. Red is suspicious of the neophyte Lightfoot infiltrating the good ol’ boys network and is vocal about his animosity toward the kid, which makes Thunderbolt bristle. While planning their heist, Red tells Thunderbolt, “When this is over, I’m gonna get that kid.” Thunderbolt, going into protective mode, shoots back. “Yeah, well, you’re gonna have to come by me first.” It’s clear Thunderbolt has let his guard down when it comes to the troubled young man who, in a sense, has given Thunderbolt a new purpose in his life. Yes, Thunderbolt wants to break into the vault and get the cash, but more for the benefit of Lightfoot than himself. He wants a better life for the kid, and Thunderbolt is intent on making it happen.

Lightfoot himself isn’t blind to the hostility directed at him from Red, and like a mischievous child poking a sleeping animal, Lightfoot takes delight in letting Red know Thunderbolt prefers his company to Red’s. At one point, Lightfoot grabs Red, pulls him close, places his hand over Red’s mouth, and kisses it, confirming he understands the jealousy Red seems to feel over the close friendship Lightfoot and Thunderbolt share. It’s worth noting that after this scene, Cimino closes in on a shot of Bridges’ rear as he walks away, a red handkerchief hanging from his right pocket. In the days before social media and mobile dating apps, gay men often signaled each other via the “hanky code.” The color of the handkerchief, as well as its placement in the right or left pocket, was an indication of a person’s sexual activity preferences. This moment in the film is perhaps Cimino’s most blatant acknowledgment of Lightfoot’s orientation, invisible to heterosexual audiences of the time, but obvious to gay moviegoers.

Jeff Bridges Does Drag

As part of the elaborate robbery scheme, the group of thieves must find a way to distract the night clerk guarding the armored vault. And what better way to do that than to dress up the already beautiful Lightfoot as a woman in a short skirt and heels to seduce the clerk? Although Red tries to humiliate Lightfoot over this assignment, Lightfoot doesn’t seem to mind, and in fact, appears to be quite proud strutting down the street in his blonde wig and white pumps. While this scene has been criticized over the years for its homophobic and transphobic undertones, Cimino doesn’t use it as mockery or comic relief. Indeed, there’s something amusing about seeing a young, buff Bridges in a form fitting floral frock, but Lightfoot in drag is the key to the group’s success or failure in pulling off the heist. His teammates depend on him to convincingly pull off his deception, and Lightfoot meets the challenge before him. He actually becomes the group’s savior in this endeavor, not an object to be scorned, and after the robbery is complete, Lightfoot comfortably snuggles up next to Thunderbolt in the front seat of the car, still in his female disguise, as they calmly exit the crime scene.

A 1970s-Style Tragic Ending

Things quickly go awry, however, when the police begin pursuing the team, with Eddie ending up dead and Red finally taking his anger out on Lightfoot in a brutal beating. Here, Cimino succumbs to the standard 1970s film rules when it comes to sexually ambiguous characters. The outliers must pay a price for bucking traditional heterosexual norms, and no happy ending must be allowed. Lightfoot’s injuries at the hands of Red are critical, and in the movie’s final scenes, the kid’s decline is swift. Thunderbolt finds a stash of money hidden for decades behind the chalkboard of a one-room schoolhouse, and for one brief, shining moment, it looks like the boys are on easy street. Thunderbolt makes Lightfoot’s dream come true by buying him a Cadillac convertible, but as the two drive away in the shiny new machine, anxious to start their new lives together, Lightfoot passes away in a moment eerily reminiscent of the final bus scene in 1969’s Midnight Cowboy, another film that told a love story between two men, outsiders in a world that will never fully accept them and who must pay the ultimate price. Like Jon Voight‘s Joe Buck, Thunderbolt is alone again, stripped of an opportunity for happiness and stability. It’s unfortunate that the Thunderbolt and Lightfoot finale falls into the same tragic formula, but it’s not surprising, given the times and Cimino’s own tendency to rarely allow his films’ lead characters a shot at redemption.

Despite this, the film deserves recognition for its determination to turn the action adventure/buddy road movie upside down and showcase the genuine tenderness between its two leading men. The movie is worth a look, not only for Bridges’ moving Oscar nominated performance, but because as Gay Pride Month approaches, it’s important to recognize and celebrate the pioneering film artists who have helped bring visibility to the LGBTQ+ community over the years.