John Ford’s classic Western, She wore a Yellow Ribbon(1949), is the second film in Ford’s famed ‘Cavalry trilogy’. It’s also one of the most visually beautiful films ever made, with John Wayne giving an extraordinary performance in the lead role.

“There are no nuances because Nathan Brittles, like Tom Dunson, is folklore and legend, They’re men working against strong handicaps. But Yellow Ribbon may be the part I’m most proud of.”

John Wayne

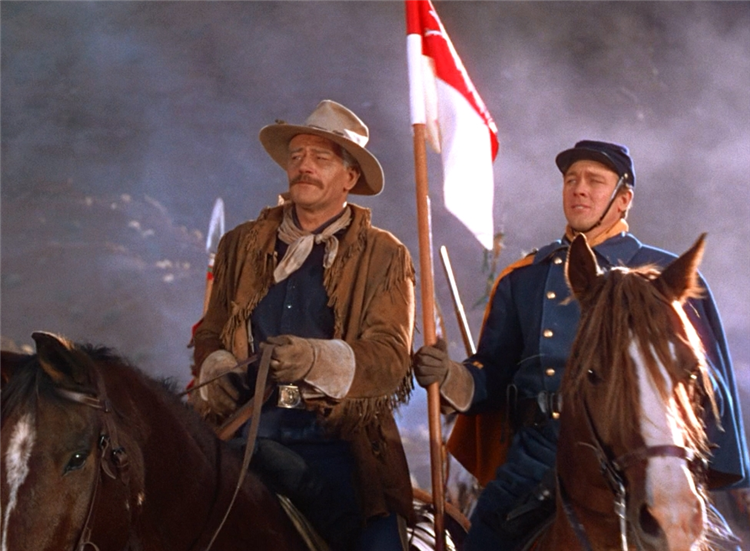

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon was the second movie in John Ford’s cavalry trilogy. The film is preceded by Fort Apache(1948) and succeeded by Rio Grande(1950)- all three movies starred John ‘Duke’ Wayne. Filmed in Ford’s beloved Monument Valley, the cast was full of Ford regulars like John Agar, Harry Carey Jr. and Victor McLaglen (as the Irish sergeant Quincannon, a role virtually reprised from Fort Apache and one he would reprise again in Rio Grande). The film, like the two other movies in the trilogy, details the struggles, defeats and triumphs of the American cavalry in the post civil war years, when they were engaged in wars with the Indian nations. But despite its familiar setting, this is a very different John Ford film. As a filmmaker, Ford has always been the ultimate traditionalist\classicalist. His films are scripted and shot in a very straightforward manner- without any tricks or jump cuts in the visuals, or in the narrative. After all, he was a major architect in designing the grammar of (American) motion pictures. His films always had a well rounded plot, with a beginning middle and an end, but “Yellow Ribbon” is one of Ford’s loosely structured, ‘ballad’ like films in which he emphasizes character over plot. It doesn’t really have a well rounded story , just a series of vignettes that establishes the lead character, Capt. Nathan Cutting Brittles(John Wayne),and follows his journey during his last days in the army. True to this spirit, It’s a film suffused with longing and remembrance, with the scenery shifting from brightly lit, magnificent red vistas of Monument valley to flaming orange sunsets. Though each film in the trilogy is a standalone film, there’s a spiritual connection between Fort Apache and “yellow Ribbon”. It’s obvious that Col. Owen Thursday, the martinet commander played by Henry Fonda in Fort Apache, was based on General George Armstrong Custer, and that the massacre of his command due to his own pig headedness at the end of that film is a direct reference to the battle of the Little Bighorn, in which Custer and his troops perished. Ironically, Yellow Ribbon begins with the news of Custer’s death, and how it has galvanized the Indian nations to unite and go to war with the American cavalry. The character of Capt. Brittles in this film is like an older version of the pragmatist and pacifist Captain Kirby, played by Wayne in Fort Apache. While that film was more intense and dark; this is a gorgeously colorful, light-hearted film. Also, like many of Ford’s greatest films that appear to be rather simple and light-weight on the surface, Yellow Ribbon too is a brilliantly crafted film of great depth and intelligence that discusses some serious themes and ideas.

The plot of the film goes something like this: the location is Fort Starke in the year 1876, and Capt. Brittles is anxiously awaiting his retirement. He has just six more days to go and his objectives for his last days of service are: to finish with honor and not get anybody (serving under him) killed. He’s also clearly worried about what comes next- there’s nothing else he wants to do, and he foresees a drift westward, maybe to California. His bumbling, drunken, first sergeant, Quincannon (Victor McLaglen) has three more weeks to go for his retirement, and Brittles is concerned about the Sergeant making it through without getting into any trouble (especially in those two weeks after Brittles’ retirement). But before he could retire in peace, his assistance is required in handling a major crisis that’s looming over the western horizon. After the defeat of General Custer at Little Big Horn, the Indian Nations have decided to unite and take on the American Cavalry, thus putting the white settlements in grave danger. Buoyed by the success of the Cheyenne over Custer, the other native tribes too come out of their reservations in hordes. The young braves of the different tribes decide to forget their mutual differences and unite in their common goal to drive the white men out of their lands. So, now, Brittles is charged with a final mission: to drive the Cheyenne and Arapaho back to their reservation. If that was not hard enough, Brittles is also tasked with an additional mission: to escort his commanding officer’s wife, Abby Allshard (Mildred Natwick), and niece, Olivia Dandridge (Joanne Dru), to an eastbound stage so that they would be safe in case of a prolonged war with the Natives. Though the film takes its name from “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon“, a popular US military song that is used to keep marching cadence, it also refers to Olivia, who wears yellow ribbons for her soldier lover. The only question is: who is that lover?. There are two of Brittles’ troop officers vying for her affections: the upper class rich kid, 2nd Lt. Ross Pennell (Harry Carey, Jr.), and the working class hero, 1st Lt. Flint Cohill (John Agar). Though Ms. Dandridge is a very fine and respectable lady, she’s quite a temptress, intentionally and mischievously whipping up jealousy and competition among the soldiers for her affections. So, when Brittles embarks on his mission, it’s natural that there is going to be bickering between Pennell and Cohill , especially with Olivia accompanying them. Though Brittles is repeatedly irritated by the behavior of his two soldiers and shows annoyance towards Olivia for being responsible for it, he would come to like her during the course of the journey.

Assisting Brittles in his mission is chief scout, Sgt. Tyree (Ben Johnson), a one-time Confederate captain of cavalry, who never misses an opportunity to address Brittles as a Yankee. He always gives sound advice to the Captain, but they are always followed by disclaimers. On their way to drop the ladies to the stagecoach, Brittles notices a large contingent of Native tribes moving in the same direction as they are. He decides to avert confrontation and chooses to go around, thus sacrificing half a day. This proves to be crucial, as by the time Brittles and his troops reaches the Stagecoach post, it has come under attack from the Natives . Everyone there is killed and the stagecoach is burned- which means that the ladies cannot go east and they will have to return to the fort with the soldiers. Having failed in both his missions, a defeated Brittles return to Fort Starke to retire, leaving his lieutenants to continue the mission in the field. But before he retires from the army, Brittles makes sure that Quincannon gets involved in a drunken brawl in the fort saloon, and is thus put in jail for two weeks, keeping him safe till his retirement. But the battle between the cavalry and the tribes rages on. Brittles, unwilling to see more lives needlessly lost, takes it upon himself to try to make peace with his old friend Native Chief Pony That Walks (Chief John Big Tree). When that too fails, he devises a risky strategy to avoid a bloody war by stampeding the Indians’ horses out of their camp, forcing the renegades to return to their reservation. The plan succeeds, and thus, Brittles manages to end his service on a triumphant note. He bids goodbye to his troops and ride off into the sunset, but his journey is interrupted by Tyree who has brought news: Brittles has being recalled to duty, as Chief of Scouts with the rank of Lt. Colonel.

There are two major highlights of this film. One: it’s extraordinary pictorial beauty and Two: A magnificent, deeply moving performance by then 42 year old Duke as the 65 year old Captain Brittles. As a visual feast, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon is unsurpassed, perhaps even by John Ford. As important as story and characters was to Ford, the landscape often emerged as the star of his movies. With She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, the director photographed Monument Valley in color for the first time. Here, Ford tries (and succeeds) to capture the West of Frederic Remington, using some of the artist’s colors and compositions; the atmosphere of frontier army life has never been more beautifully evoked on film. This film being more of a richly realized ‘Character study’, Ford grounds the lead protagonist with the magnificent geography; as is the case with a lot of Ford’s protagonists, the external journey is a metaphor for their internal journey, with the backdrop reflecting their emotional state. So It’s no surprise that the film has so many scenes set in the backdrop of the sunset, as it is about the final moments in a soldier’s career. Winton C. Hoch, who had first collaborated with Ford on 3 Godfathers, photographed this film in lush 3 strip Technicolor process.. The scene of the cavalrymen leading their mounts through a storm, with lightning flashes in an awesome sky, became a classic moment in cinema history and helped win Hoch an Academy Award. According to Ford, Hoch shot the celebrated thunderstorm sequence with “under protest” written on the clapperboard. The way Ford told it: Hoch didn’t think there was enough light to shoot the sudden storm that arose on location in Monument Valley, and it could seriously damage the cameras. Hoch has always disputed Ford’s version of events claiming that he has never shot a film “Under Protest“. Actors like Harry Carey Jr. who were in the scene has confirmed Hoch’s version, and when one takes into account that Ford was as good a storyteller off-screen as he was on-screen, maybe there’s more merit in Hoch’s story. Whatever the truth, it goes without saying that the Monument valley has never looked so beautiful. one is simply filled with awe as Ford fills the screen with one ravishing image after another: The shots of the cavalry moving through the valley as the red dust envelopes them; The first sighting of a herd of Buffaloes; or a terrific action sequence where Ben Johnson is chased by a group of Cheyenne dog soldiers; all attest to Ford’s visual artistry. And it’s not just in the shooting of landscapes that Ford excels, the film also has a lovely sense of lived life: the dogs that are forever hanging around the regiment, the design and set dressing of the Fort, etc. attest to this. Then there’s the Shakespearean Tragic-comic nature of Ford’s films, where a highly emotionally charged scene is contrasted with some low-bro comedy. Here, the juxtaposition of two “retirement scenes” perfectly illustrates this . The first scene, with Wayne s aging Captain Brittles inspecting his troops for the last time, is unabashedly sentimental, but the second, with McLaglen’s Sergeant Quincannon sparking a drunken brawl in the Fort Starke saloon, is broad slapstick comedy. The Victor McLaglen brand of Irish comedy is always considered the weak spot in Ford’s films, and frankly it has dated very badly and makes up for the worst portions of this film, but it used by Ford to create a counterpoint: The ritualistic award giving and speech making of the first scene are parodied by the ritualistic drinking and brawling of the second. And while Ford introduces a few comic touches into Brittles’ farewell, he gives a darker shading to Quincannon’s by having Brittles admit setting up the brawl to put Quincannon in the guardhouse and out of harm’s way until his time to retire; a deeply melancholic look at retirement as both tragic and ridiculous.

This is also one of Ford’s least violent westerns. There’s hardly any bloodshed, Wayne’s Captain always making sure that his troops fire over the head of the native warriors when they come charging in. He just wants to drive them back, not to kill them. And as in Fort Apache, where we had Wayne’s character going on a peace mission, there is a similar scene here as well. But here, the scene is rather funny and is used to establish the similarities existing between two old guys of different races. It’s the scene were Brittles meets Pony that walks to convince him to call off his warriors. Pony that walks calls himself a Christian and greets him with a hallelujah. He tells Brittles that the young red men have become like young white men, who no longer accepts the advice of old people. He suggests that they both go away together and spend their last days drinking and hunting; again reasserting the theme of the film, about aging and an old world being replaced by the New. These two films are a major turning point in the depiction of native Americans in Hollywood movies. They were given a voice and treated with dignity, and the mistakes committed by the American government in their treatment was criticized. Which is why it’s shocking to see Ford going back to treating them as nameless, faceless violent hordes in Rio Grande, the last and the least impressive of the trilogy. There has always been this eccentricity in Ford’s filmography; for instance, a dreamy romance like The Quiet Man followed by a dark and violent epic The Searchers.

Now coming to John Wayne’s performance, the film should be made compulsory viewing for all those who claim that John Wayne cannot act. The character of Capt. Nathan Brittles was one of Duke’s favorite roles. His Brittles embodies abstract qualities like honor and loyalty and Wayne makes them concrete with a total mastery of effect. He played a character who was more than 20 years his senior at the time. The officer has spent forty years in the cavalry; he understands natives and is sensitive to the welfare and needs of the men serving under him. Brittles was a role that required authority but also tenderness and emotional depth. His attitude directly contradicts his motto: “Never apologize, it’s a sign of weakness.”. There are two major scenes that bring out the best in Wayne as an actor. First is a graveyard scene , where the widowed officer visits the burial site of his deceased wife and children. No reason is given for their death, but it’s assumed that they died of some epidemic; as marked on their gravestone, 5 days separate the death of his wife and the children in 1867. Brittles is talking to his wife, directly addressing her by her name Mary, about his insecurities regarding his retirement and also about a soldier who died along with Custer whom they both happened to know. The intensely personal moment could have become overly sentimental, but Wayne plays it at a right pitch in a very relaxed and casual manner (he is watering the plants as he’s talking), without overemphasizing the emotions. Brittles is interrupted by Olivia who has come to apologize and brought a flowerpot as a gift for him. The scene is classic Ford, with Olivia’s shadow slowly falling on Mary’s grave – Ford would repeat this shot in The Searchers, where Scar’s shadow falls on little Debbie when she is hiding in the graveyard – establishing a connection between these two characters, which is confirmed by Brittles at the end of the scene, when he tells his wife that Olivia reminds him a lot of her. Ford’s staging and Wayne’s deeply moving performance makes sure that the graveyard sequence comes across magnificently.

The second scene is where Brittles bids farewell to his troops. As retirement gift, his men give him an engraved silver watch, which brings tears to the old man’s eyes. The men tell him that there is an inscription on the back of the watch. What happens next is a ‘production’ in it’s own right. First Brittles tries to read the inscription, but his eyesight is failing and is unable to read. Embarrassed and a little shy, he slowly takes out his glasses – carefully looking around if anybody is watching him, he slowly puts on the glasses and with great difficulty reads the words “Lest we forget“. He chokes up while saying those words. Wayne himself was overcome by emotion when playing the scene and he felt that the moment demonstrated a soldier’s finer qualities. And in every scene after that, Brittles will be seen, rather ostentatiously, reaching into his pocket and checking the time, as he does at the end of the film, saying, “Let’s see what time it is by my brand new silver watch. Three minutes after twelve. I’ve been a civilian for three minutes. Hard to believe.” Then he bids farewell and ride off into the sunset. Duke wanted the film to end there , but according to him, Ford wanted to add that final scene where Brittles is recalled to duty; an ending which Duke referred to as BS. Ford would later blame producer Merian Cooper for forcing him to do that ending: where Tyree should chase after the retired officer and bring him back to the post for another assignment. But I have a feeling that Ford very closely identified with the character of Brittles. He was the same age as Brittles and he didn’t want his doppelganger to retire and ride off into the sunset, as he himself wasn’t prepared to do that. And eventually, he would prove that he still had about fifteen years of solid filmmaking left in him. All those classics like The Quiet Man, The Searchers and The Man who Liberty Valance were made in his late sixties.

Ford and Wayne shared a long, prosperous and quite complex relationship that started off with Stagecoach in 1939. Ford made Wayne a star and played an important part in building the “John Wayne” persona. But Ford was always dismissive of Wayne as an actor and used to treat him rather cruelly on the sets. And when it came came to this film, Ford didn’t want Wayne at all; he was more interested in casting Henry Fonda who was a good friend and whom he considered a great actor. But that changed when Ford saw Howard Hawks’ Red River in which Wayne had given a fantastic performance playing an aging patriarch. Wayne always believed that the director cast him in the part because Ford wanted to be responsible for Duke’s topping his performance in Red River. It succeeded, for there was talk of an Oscar nomination for Wayne. He did get nominated that year, but not for Yellow Ribbon, but for Sands of Iwo Jima. Unfortunately, he lost the Oscar to Broderick Crawford for All the King’s men (A film that Duke despised for it’s desecration of American way of life). Though he was appreciated for his performance in Yellow Ribbon, Duke remained bitter about the fact that he never got the appreciation he deserved for his performance , as neither the audience nor the critics were interested in seeing him expand his range as an actor. After this film, he would go back to playing the typical “John Wayne” roles. But he got a much bigger ‘award’ that year that must have been more valuable to Duke than any Oscar. After the filming on Yellow Ribbon was complete, John Ford presented Duke with a more personal award. The director sent Wayne a cake bearing a single candle and the message: “You’re an actor now.”