The West is a little lonelier following the passing of one of its heroes, the great American actor Dennis Weaver. Weaver, 81, passed away at his home in Ridgway, Colorado, on February 24.

In his time, Weaver was a pilot, a veteran of World War II, a vastly popular entertainer on television and in the movies, a singer-songwriter and something of a philosopher. He later became one of the country’s most eloquent spokesmen for environmental change.

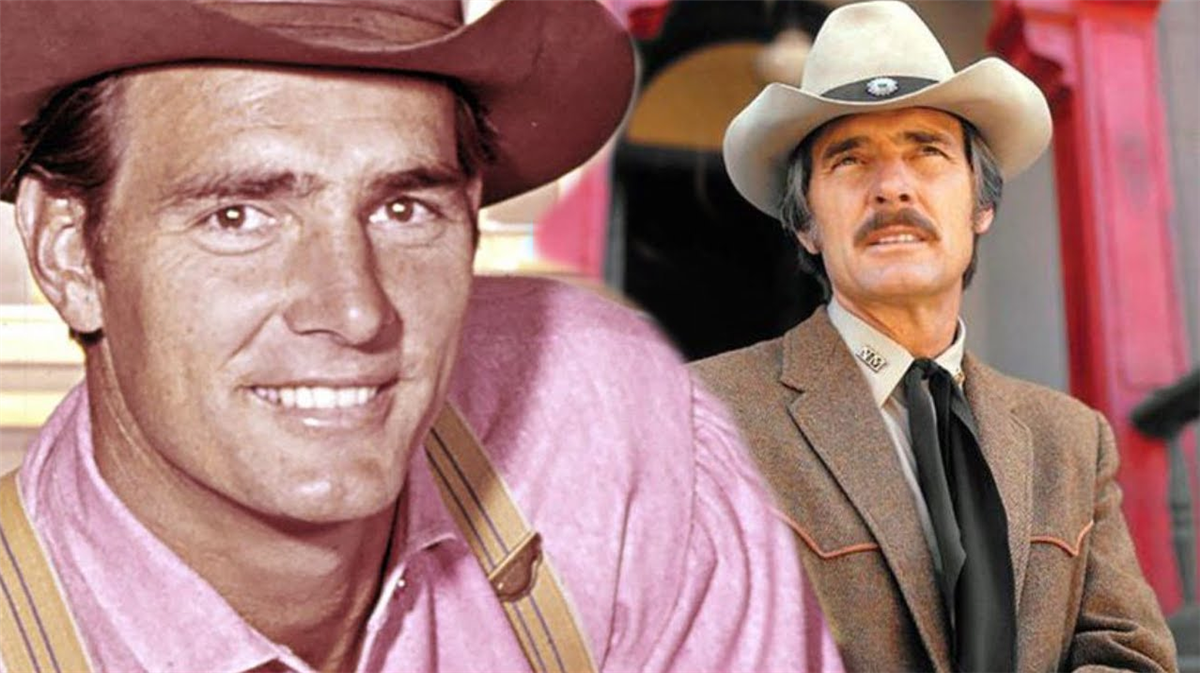

Weaver is best known for his memorable portrayals of larger-than-life characters, most notably Deputy Goode in “Gunsmoke,” Tom Wedloe in “Gentle Ben,” and in later life, Sam McCloud, a New Mexico cop on the streets of New York. “McCloud,” in which Weaver was seldom without his horse, his cowboy hat and a sheepskin coat, carried the same western sentiments as the talented actor who played him.

While his television work defined his career, Weaver’s acting career was expansive. His early work included acting on stage opposite Shelley Winters in “A Streetcar Named Desire” and a small role in Orson Welles’ 1957 classic, “Touch of Evil.” He later went on to play the lead role in a tense, celebrated television movie called “Duel,” directed by future Hollywood director Steven Spielberg. His rangy western features also led to roles in “Centennial” and “Lonesome Dove,” in which the Missouri-born actor played Buffalo Bill Cody.

Three miracles

Later roles would recall his brief flying career, which was brought about by World War II. During his career, Weaver appeared in “The Bridges at Toko-Ri,” which centered on the bombing of a set of heavily defended bridges during the Korean War, and in “Pearl,” which examined the build-up to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that brought America into the war.

Weaver’s own flying career wasn’t quite as glamorous, but it was filled with jeopardy. Long before he claimed fame as an actor, he joined the Naval Air Corps, at 18, and entered the V-5 flight training program.

While he was stationed at the University of Colorado at Boulder, Weaver learned to fly a Piper Cub. A flight in that aircraft was just one of three nearly disastrous flights for him.

He recalled the flight in his engaging 2001 memoir, “All the World’s a Stage.” On a perfect, clear day, as Weaver was taking off to fly his first solo along the Flatirons, his instructor told him, “You’re on your own, kid, and don’t forget to spin.”

But as he attempted the maneuver at 6,000 feet, the plane started spinning out of control, heading right for the brown fields below.

“Overlapping thoughts of terror raced through my mind. … Am I going to eat it on my first solo flight? Should I bail out? Will I get washed out? Will my damn parachute work?” Weaver wrote later.

Miraculously, the plane leveled out and a wrung-out Weaver managed to take the plane back to the airport. On shaking legs, he passed the flight board to find his plane, number 23, marked with a warning, “Do not spin plane 23!”

After Weaver had pre-flight training in Oakland and primary training in Livermore, Calif., he got his wings in Corpus Christi, Texas. He was next stationed at Opa-locka Naval Air Station, near Miami, Fla., where he and his fellow pilots would stage mock dogfights to pass the time. He was making a dive on one of his buddies when he nearly ended his acting career before it ever started.

“I went screaming past him,” he wrote. “I was looking to see where he was, so he wouldn’t get on my tail, when suddenly something made me turn around and look straight ahead. Holy cow, there was this pink stucco house. It was about two seconds away, and I was headed right for it! You never saw anybody jerk a stick back so fast—I damned near broke it! The nose of the F-4F arched skyward as it screamed past the pink house, missing it by a whisker.”

That’s two miracles, but it wasn’t the last one. While Weaver was still at Opa-locka, he spent another afternoon making touch-and-go landings to simulate a carrier landing. As he came down for a landing in the F-4F, the manual landing gear folded like a tent, forcing Weaver into a screaming, fiery, gearless landing in an aircraft with its fuel tank in its belly.

“It felt much like a horse when it steps in a gopher hole and crumples to its knees,” he wrote. “I thought I was dead for sure. … All I could think while my plane was skidding down the runway was, ‘I’ve got to leave this baby as quickly as I can before I’m engulfed in flames.’”

Soon afterwards, the war in Japan ended with the bombing of Hiroshima, and Weaver snapped up an offer to leave the Navy. When asked about his role in the war, Weaver said, “It wasn’t much, but it sure was interesting.”

The leading man

In 1945, he married Gerry Stowell, with whom he had three sons, Rick, Rob and Rusty. In 1948, he narrowly missed out on the Olympics, but competed in the final trials of the decathlon. Pursuing his passion for acting, Weaver headed for New York, where he studied at the Actor’s Studio under Lee Strasberg and landed roles in a number of stage plays, including “Come Back, Little Sheba” with Shirley Booth. That experience led Universal Studios to sign him in 1952. Weaver acted in a number of westerns while with Universal.

By 1955, he was living in Hollywood, delivering flowers for a shop whose customers included Lucille Ball and John Ford. That year, he landed his first big role, as Chester Goode in “Gunsmoke.” The series was an immediate success for CBS. Weaver won his first Emmy for the role in 1959.

“One of the main reasons why people enjoyed Chester was because he allowed them to feel superior,” Weaver said. “You see, he wasn’t the brightest person in the world, but there was a simple goodness about him.”

He left “Gunsmoke” in 1964 and appeared in several other series, including “Kentucky Jones,” “Emerald Point NAS” and “Stone and Buck James,” but turned down David Janssen’s role in “The Fugitive.” In 1970, he landed his most personally satisfying role as Deputy Marshal Sam McCloud, which was inspired by the Clint Eastwood film, “Coogan’s Bluff.” Weaver’s affable western style was even more memorable because of the series’ big-city setting.

“For seven years, McCloud was pure joy,” Weaver said. “It allowed me to do what I got into the business to do: to play the leading man.”

Around the same time, he served as president of the Screen Actors Guild. Weaver also pursued his own interests in singing and songwriting, demonstrating his talents on “Hee Haw,” in several television music specials, and on his own country albums. He was good friends with John Denver, who once offered Weaver “Back Home Again” for one of his albums.

In a break from his usual western characters, Weaver played the lead in Steven Spielberg’s “Duel” in 1971. The movie pitted a traveling salesman against a dangerous, unknown truck driver.

At an age when most actors consider retiring, Weaver kept up his acting, appearing in “Lonesome Dove,” a television remake of “The Virginian,” and was the voice of Buck McCoy in the 2002 episode, “The Latest Gun in the West” on “The Simpsons.”

“I feel so blessed to have had such a rewarding career,” Weaver said. “It’s been an exciting life, a terrific run, and I’m most grateful.”

The humanitarian

Weaver was a model for Hollywood activism. In 1972, with his own social conscience growing, he campaigned on behalf of Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern. He joined a host of other high-profile supporters including Leonard Nimoy, Shirley MacLaine and Warren Beatty.

A proponent of a healthy lifestyle, Weaver became a vegetarian in 1958 and practiced yoga and meditation throughout his life. He wrote extensively about his spiritual beliefs in “All the World’s a Stage.” He was involved with John Denver’s Windstar Foundation and helped co-found L.I.F.E. (Love is Feeding Everyone), which fed 180,000 needy people per week in Los Angeles.

The actor was also well known as a pioneering environmentalist, promoting alternate fuels, sustainable living and other “green” methodologies long before they became fashionable.

In 1994, he and Gerry founded his own educational institution, the Institute of Ecolonomics. The organization’s name combined his interests in ecology and economics. Weaver spoke extensively about the environment to everyone from schoolchildren to the United Nations.

Living what he preached, he drove a Toyota Prius and built “The Earth Ship,” his personal home in Ridgway, which demonstrated his commitment to the environment. Once called “The Michelin Mansion,” it was constructed partially from 3,000 used tires and incorporated recycled materials, solar technology and other environmentally responsible features that promoted sustainable living.

In 2003, Weaver led a fleet of alternative-fueled vehicles on a whistle-stop tour to increase awareness of oil dependency and joined forces with Willie Nelson to promote biodiesel as a fuel.

“This is the most exciting time in the history of the human species,” Weaver said. “The potential for human growth, for true happiness, and sustained fulfillment has never been greater. However, it is also the most dangerous time, for we humans are in charge; we are at the helm of the ship. Whether we get safely through the rough waters ahead depends on the choices we make now.”

Weaver also won much acclaim for his efforts both on and off the stage. In 1986, he received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and he was inducted into the Western Performers Hall of Fame. He won awards including the Screen Actors Guild Award, the Western Heritage Award, and the Louella Parsons Award from the Hollywood Women’s Press Association.

Dennis Weaver leaves behind a profound legacy. He was brave, resourceful, funny, charming and kind—much like the unforgettable characters he played. In his long journey to become the man he wanted to be, the great actor elevated not only the art of acting that he loved, but also his fellow man. Truly “the best of the west,” he’s one cowboy who will be truly missed.