John Wayne starred in 169 movies, playing so many heroic cowboys that many Americans believed he had single-handedly won the West – and he came to believe it.

Yet Wayne was living a lie. Behind closed doors the man born Marion Morrison was a restless, melancholy, troubled actor struggling to live up to the screen persona he had created, a bombshell new biography reveals.

In John Wayne: The Life And Legend author Scott Eyman exposes a John Wayne very few knew.

Haunted by three failed marriages and bad relations with his children, he always struggled to win the respect he believed he deserved and felt forced to hide his sensitivity and artistic leanings.

For 25 years until 1974 he was one of the world’s top box-office stars, yet he worked almost until his ԁеаtһ not because of a love of acting, but because bad business deals and betrayals by friends meant that he never felt financially secure.

Instead the movie legend battled against his inner demons trying to live up to the John Wayne the world thought him to be. Despite his success he was tormented by his failures.

“The guy you see on the screen really isn’t me,” Wayne once admitted.

“I’m Duke Morrison and I never was and never will be a film personality like John Wayne.

“I know him well.

“I’m one of his closest students.

“I have to be.

“I make a living out of him.”

But playing the role of John Wayne off screen was tearing the actor apart, the new book reveals.

Wayne starred in Second World Wаr drama The Sands Of Iwo Jima, winning an Oscar nomination for his part as the quintessential US Marine.

In reality the actor was guilt-ridden having avoided military service during the conflict, staying home with his children while other stars from Henry Fonda to Ronald Reagan enlisted.

Wayne preferred the comfort of a yacht rather than a saddle and while his on-screen kisses may have been bashful, off screen he was a sex-hungry, unfaithful husband.

Wayne’s inner turmoil drove him to extremes.

He smoked up to six packs of cigarettes a day, consumed heroic quantities of booze and food, and made harsh demands of those around him.

He often woke at dawn and roused his family because he disliked being alone.

His second wife Esperanza Diaz accused him of infidelity, violence and emotional cruelty.

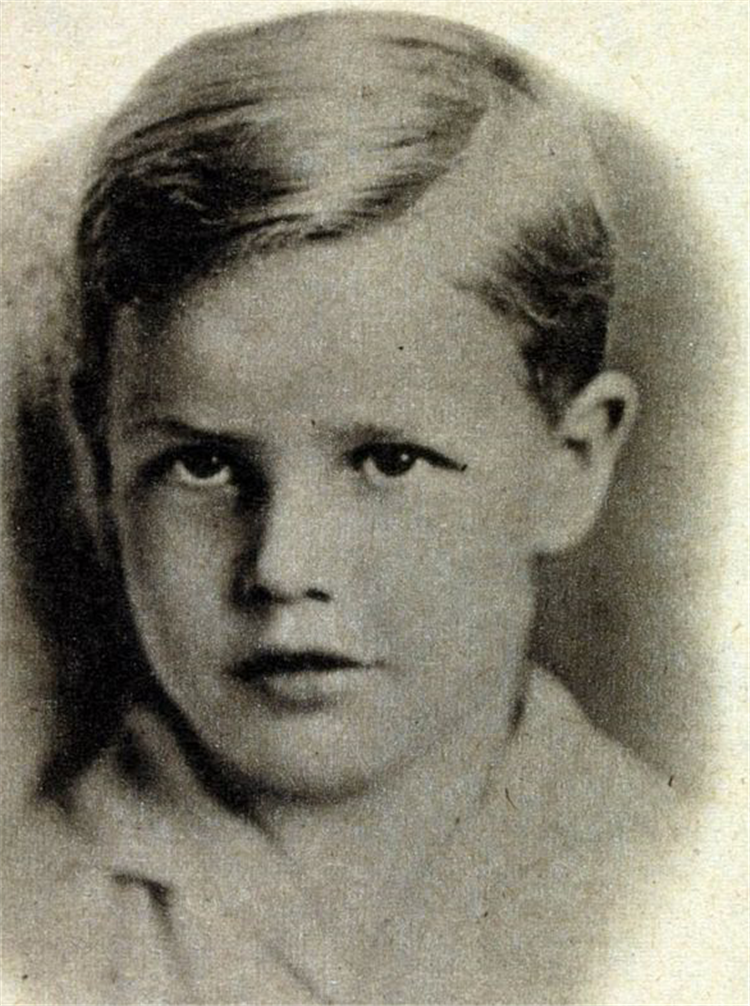

Born in Winterset, Iowa in 1907 he moved with his family to California at seven, the college football star worked as a movie prop-man and extra before being spotted by director John Ford who launched him as an actor.

Yet before his breakout role in 1939 Western drama Stagecoach, Wayne spent a decade honing his persona: “A voice, a name, a walk that would grow more pronounced in the future, an overall attitude,” writes Eyman.

A symbol of American machismo, simultaneously an outsider and an authority figure, Wayne played a series of idealised frontier Western heroes on screen.

He summed up his persona as “the character the average man wants himself, his brother or his kid to be.

“Always walk with your head held high.

“Look everybody straight in the eye.

“Never double-cross a pal.”

But Wayne’s jingoistic patriotism was also his undoing.

He spent 10 years and £1.2million of his own money making 1960 flop The Alamo.

“Everybody made money from it but me,” Wayne lamented.

His 1968 pro-Vietnam Wаr movie The Green Berets at least made money but alienated a younger generation that never forgave him.

Wayne endured the constant failure to live up to his screen persona.

When diagnosed with lung cancer in 1964 he poignantly recalled: “I sat there trying to be John Wayne.”

Surgery removed part of a lung but Wayne continued wheezing through a succession of mediocre Westerns to pay the bills, while rejecting stronger roles that didn’t fit his image, including Dirty Harry and The Dirty Dozen.

“He intended to play only men who mirrored his own beliefs, his own values,” says Eyman.

Yet while Wayne’s on-screen character was a man of constrained violence, in real life the actor was quick to apologise if his temper exploded.

From 1951 drama The Quiet Man until his ԁеаtһ from stomach cancer in 1979 at 72, Wayne gave every cast and crew member on all his movies a personalised coffee mug as a thank-you.

On screen he was a man of action and few words, yet off camera he played chess and bridge, would quote Shakespeare and Dickens and had a penchant for Tolkien.

Fans of his Westerns never knew that Wayne collected Eastern woodblock prints and native American kachina dolls.

The son of impoverished parents who struggled throughout their lives, Wayne never lost his passion for catalogue shopping, buying gifts for family and friends until “mail-order packages would arrive in bunches, 10 or 20 at a time,” reveals Eyman.

But Wayne could not find happinessin a mail-order catalogue and his personal life was tormented.

His mother Mary was cold and hypercritical no matter how successful he became.

She accepted Wayne’s frequent generosity with a sneer.

His father Clyde Morrison was a business failure who ԁıеԁ before seeing his son achieve stardom.

Wayne dedicated himself to his career but as a frequently absent father had a troubled relationship with his seven children.

Fears of inadequacy drove him to affairs that destroyed his three marriages.

A fling with screen siren Marlene Dietrich ended with Wayne being dumped by his first wife Josephine Saenz.

Though Wayne emboԁıеԁ machismo on screen it was Dietrich who was the sexual aggressor pursuing the actor, reveals Eyman.

When Dietrich spotted Wayne at a Hollywood restaurant she turned to her friend, a top film director, and purred: “Daddy, buy me that.”

They starred together in the 1940 hit Seven Sinners and Wayne began cheating on his wife.

When Wayne came on set Dietrich would leap into his arms and wrap her legs around him and he told friends that she gave him the best sexual experience of his life.

He never even complained when Dietrich spent time with close lesbian friends.

But the real-life Wayne could be indecisive, promising his wife to end the affair if only she stopped complaining about the German actress.

When his wife’s protests continued, Wayne admitted: “That’s when I knew the marriage was over.”

His on-off affair with Dietrich, however, spanned 20 years.

His second marriage, to Esperanza Diaz, was a volatile seven-year roller-coaster and his third wife Peruvian-born actress Pilar Pallette left him six years before his ԁеаtһ although they never divorced.

She complained that he was often absent, even when not working.

Wayne claimed family always came first but Pilar said: “Although he loved the children and me, there were times when we couldn’t compete with his career or his devotion to the Republican Party.”

A womaniser to the end, he spent his final years living with his secretary Pat Stacy.

But playing John Wayne was a full-time job and the actor spent much of his career battling to live up to the John Wayne fans knew.

He wore a wig in every movie after 1948, had plastic surgery to remove crows’ feet around his eyes in 1969 and in later years wore 3in lifts in his shoes as his 6ft 4in frame shrank with age.

Only at the end of his career did he dare to break away from his selfimposed rule of portraying all-American role models, winning an Oscar for 1969 western True Grit, playing over-the-hill drunkard Marshal Rooster Cogburn.

Wayne called it “my first decent role in 20 years – and my first chance to play a character role instead of John Wayne.”

But if playing John Wayne was the actor’s greatest role, it was also one he struggled with for a lifetime and never felt he mastered.