The conventional wisdom on John Wayne’s acting abilities holds that he was a severely limited performer who leaned heavily into his persona to the point of self-parody. Moviegoers who didn’t grow up watching his movies (or have parents who grew up watching his movies) tend to view him as a relic of a blessedly bygone era at best or a rampaging racist who made movies that whitewashed the genocidal exercise of Westward Expansion. They basically have no use for him at all.

Everyone has their own threshold for separating the art from the artist, but I think holding his personal views against A-class Westerns that told a more complicated tale than the average B oater is a mistake. Furthermore, I’d argue that there was nuance to his swagger. Wayne didn’t become the biggest movie star of the ’40s and ’50s because he stood for conservative American values. He was huge because he knew how to modulate his persona from role to role while maintaining the macho essence that drew audiences to him in the first place.

The Duke had an actual acting process

If you’ve read a Wayne biography, you’ll find most of his co-stars to be hugely complimentary of, if not downright amazed by his ability to mold a character to suit his particular needs. In Scott Eyman’s “John Wayne: The Life and Legend,” Ron Howard, who worked with the star on his swan song, Don Siegel’s “The Shootist,” explains how he came to learn the art of The Duke’s acting. As he told Eyman:

“When we ran lines, and [Wayne] was sorting out his performance, sometimes there would be an awkward moment that was a little stilted – a speech that wasn’t quite landing. And he would say, ‘Let me try again.’ And he would put that hitch in, that pause that he had in his speeches, and the line would suddenly take on power. He understood how to work with the rhythms of speech, to find a surprising nuance in the moment of the dialogue.”

According to Howard, it was Wayne’s “way of putting the focus on an aspect of a verbal moment.” When the actor-director has revisited Wayne’s films over the years, he realized that these minor tweaks could earn a huge laugh or make him appear vulnerable. “It was interesting,” said Howard. “And It was art.”

It took skill to be John Wayne

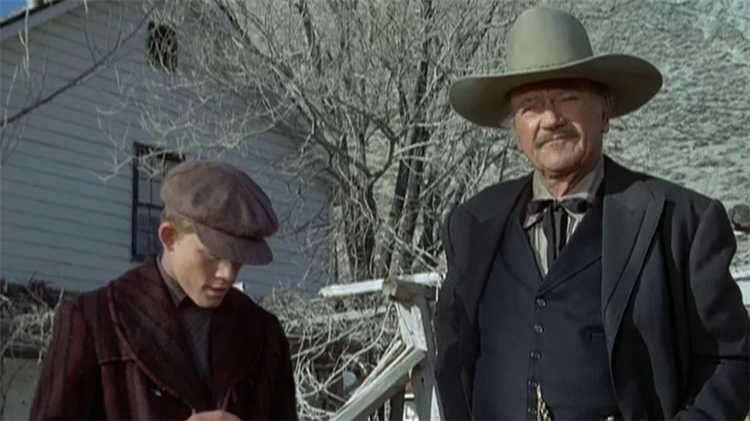

Wayne’s peers generally agreed with Howard’s assessment. The Duke earned two Oscar nominations for Best Actor during his career, winning in 1969 as the cantankerous U.S. Marshal Rooster Cogburn in “True Grit.” That he won for hamming it up late in his career instead of for his finely shaded portrayal of antihero/racist Ethan Edwards in John Ford’s “The Searchers” (which was completely snubbed by the Academy) suggests that they, like the moviegoing public, preferred Wayne as a straight-up hero.

Again, everyone has a certain tolerance level for how much off-screen awfulness they can compartmentalize, but to dismiss Wayne’s performances as caricature is simply wrong. He wasn’t afraid to play unlikable characters, perhaps because these people allowed him to explore facets of his own personality that he knew, deep down, were troubling.