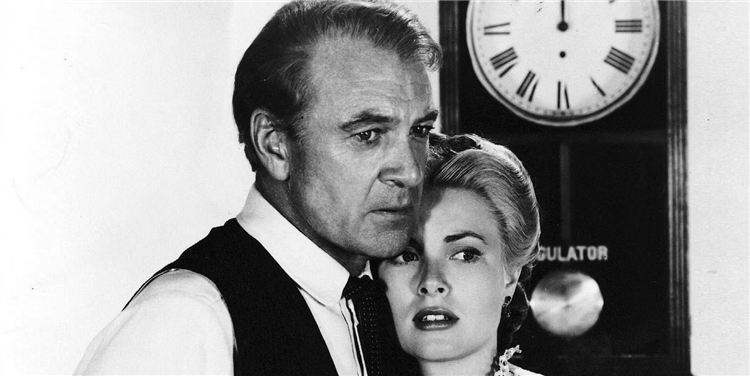

High Noon certainly felt like an elevated take on the genre, as it took more time to consider misconceptions about masculine stereotypes. It wasn’t like westerns were treated as a second class genre, but High Noon specifically attacked the notion that the gunslinger had to be an unflinching tough guy. Gary Cooper was best known at the time for playing sensitive, humble characters that emerge from nothing to achieve success (with Pride of the Yankees, Sergeant York, and For Whom The Bell Tolls as prime examples). Cooper’s High Noon character, Marshall Will Kane, is caught between his personal and professional obligations. Can he save Hadleyville from the ruthless outlaw Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) without giving up his beloved bride, Amy Fowler (Grace Kelly)?

High Noon ultimately has a positive depiction of the individual, and not the law. This is perhaps what rubbed Wayne and Hawks the wrong way. By the end of High Noon, Kane has killed Miller, saved the town, and reunited with Amy. Amy shows her support for her husband’s bravery without specifically lionizing the role of law enforcement. In one of the film’s quintessential shots, Kane casts aside his badge into the dirt before departing with Amy in a wagon. Heroism isn’t defined by the badge. This was an important message to share within the social climate of the era, where the debate over police brutality would soon reach a national stage. When Kenneth Branagh

referenced

High Noon in

Belfast, it wasn’t just a personal in-joke. The

High Noon theme plays as

Jamie Dornan’s character stands up for his family in the midst of persecution.

However, Rio Bravo isn’t just an aggressive retcon of these ideas. While Wayne’s legacy is complex and difficult to reckon with, he frequently seemed ignorant of the subtext of his own films. The Searchers is a searing indictment of racism and extremism, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is a subversive farewell to the Golden Age of westerns. Compared to the steely nature of other westerns at the time, Rio Bravo is wacky, weird, and utterly hilarious. It’s no wonder why Tarantino seemed to take such a personal liking to it; the razor sharp one-liners are just as exciting as the third act set piece.

While Rio Bravo isn’t as aggressively subversive as High Noon, it also helped deconstruct stereotypes of what a “hero” looked like. Hawks’ chief criticism of High Noon was that he didn’t feel that a hero should question his duty. The characters in Rio Bravo offer to stand by their post to imprison Joe Burdette (Claude Akins), no matter what the cost. However, these heroes are a bit of a motley crew. Joining Wayne’s character, John Chance, are an alcoholic has-been (Dean Martin’s “Dude”), a disabled older man (Walter Brennan’s “Stumpy”), and a hot-headed younger man (Ricky Nelson’s Colorado Ryan). Compared to other Wayne films, Rio Bravo even sneaks in a relatively positive depiction of the Mexican innkeeper Carlos Robante (Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez) and his wife, Consuelo (Estelita Rodriguez).

Ironically, Rio Bravo actually holds up better than High Noon when it comes to painting a picture of a more complex villain. High Noon’s Frank Miller is the type of outlaw that already felt outdated at the time. By comparison, Joe in Rio Bravo is a spoiled rich kid who thinks that his wealth grants him exemption from justice. It’s remarkably a searing indictment of capitalism, as Chance and his allies have to ward off an army sent by Joe’s brother, the prominent land baron Nathan (John Russell). The law is apparently flexible for anyone with the money to pay for it.

Rio Bravo may have emerged as a counterargument to the themes that High Noon addressed, but both films are an essential part of the western canon. Instead of relying on nostalgia, these two classics subverted stereotypes, and spoke to modern themes without sacrificing the genre’s inherent joys. Whether you are a die-hard John Wayne fan or an ardent Gary Cooper follower, it’s a terrific double feature.