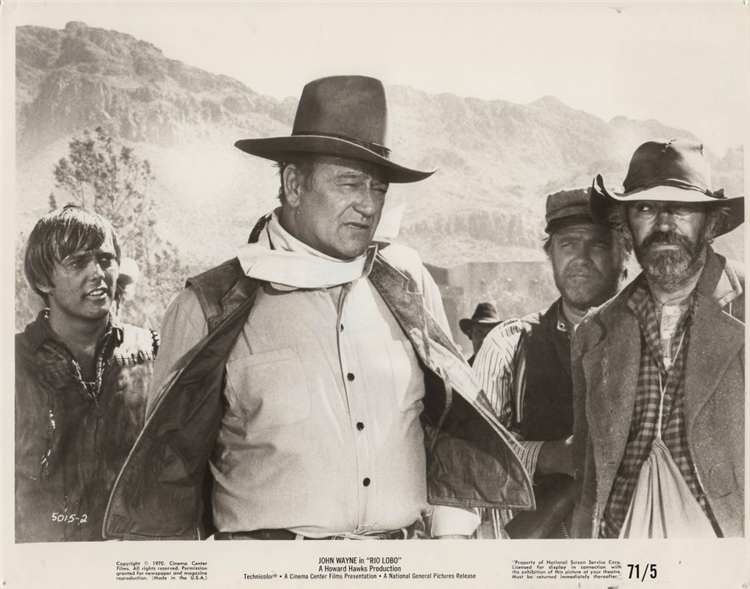

Rio Lobo(1970), starring John Wayne, Jack Elam, Jorge Rivero and Christopher Mitchum, marked the fifth and final collaboration between John Wayne and Director Howard Hawks. This Western is also the last theatrically released feature film directed by Hawks.

“I’ve been called a lot of things, but not ‘comfortable’!“

First there was “Rio Bravo(1959),” then came “El Dorado(1967)” and finally “Rio Lobo(1970)”; all three were Westerns directed by Howard Hawks with John ‘Duke’ Wayne in the lead, and were written by the eminent female author, Leigh Brackett. Additionally, all three has the same plot, with slight variations in scenarios and characterizations. Hawks is one of the most revered directors from Hollywood’s classical period, and he has made films across many genres, but each one of them possessed his distinct stamp. To be honest, Hawks may have made just three or four original movies, the rest are all derivatives and composites of those movies. Hawks, who had a prolific and very successful career till the end of the 1940s, had some setbacks in the 50s, which drove him away from filmmaking for about four years. But when he made a comeback to direction with “Rio Bravo,” he hit upon a successful formula that mixed elements from his Westerns and screwball comedies. The film was a heightened meditation on Hawks’ pet themes like professionalism, male bonding in time of crisis, and the strong, independent ‘Hawksian’ woman- within the template of a ‘Town’ Western, in which a besieged Sherriff uphold his professional duty at all costs with the support of some colorful and over-the-hill characters. After the success of the film Hawks just continued to milk the same formula in film after film for the rest of his career. When he had two flops back to back in the mid 60s, he returned to the “Rio Bravo” well to draw some more of the same water, albeit with a different cast and a more comedic take. That film was once again a big hit, so naturally for his next ‘Western’ teaming with Duke, titled “Rio Lobo,” he decided to use the same formula, which he had developed with Brackett (who along with Burton Wohl would write this film). The film, incidentally, turned out to be Hawks’ last film- though he hadn’t planned it that way. He had planned to make many more movies in the 1970s, but he never could mount another production before he died in 1977.

“Rio Lobo” is set at the tail end of the American Civil War and the film has Duke playing Union Colonel Cord McNally. The Union Gold shipments transported by train under Cord’s watch are being systematically hijacked by the Confederates. Cord believes that there’s a traitor who’s feeding information to the opposite side, and hence he has increased the security around the shipments. But that doesn’t seem to deter the Confederates; and, as the film begins, the Rebs led by Capt. Pierre Cordona and Sgt. Tuscarora Phillips are seen affecting a spectacular (and quite ingenious) Train hijack- ropes, trees, grease and Hornet’s nest are all weapons for the hijackers. During the hijack, one of Cord’s friends, Lt. Ned Forsythe, is killed while jumping out of the train. Cord pursues the confederates with his men, but during the pursuit his squad is spread thinner and thinner until he is left on his own, and is easily captured by the Rebs. After Cordona and his men capture him, Cord tricks them by leading them into a Union camp and raising the alarm. Though Cord repeatedly questions them, neither Cordona nor Tuscarora reveal the identity of the informer in Cord’s army. But Despite their altercation, the three men gain a mutual respect for each other. When the war ends, the two Confederates (who were POWs) are released from prison camp; and Cord is there to greet them upon their release. They have a friendly chat, and this time the ex-Confederates reveal the identity of the Union informers (there are two of them)- but they can only provide a physical description. Some time later, Cord gets a message from Cordona through his friend, Pat Cronin, the sheriff of Blackthorne, Texas that he has identified one of the informers. Cord arrives in Blackthorne to meet Cordona, but before they could meet, they get involved in a gunfight involving a lady named Shasta, and the corrupt deputies of the neighboring town of ‘Rio Lobo.’ After they have dispatched the deputies, Cordona identifies one of them as the informer feeding them information on Union Gold shipments during war.

Now one more informer left to be revealed, Cord is forced to join Cordona and Shasta on a trip to Rio Lobo, where the town’s nasty Sheriff, Hendricks, in cahoots with a wealthy land baron, Ketcham, is stealing land from the rest of the ranchers- one of whom is their Ex-Confederate pal, Tuscarora’s father, old man Phillips. Upon arriving in Rio Lobo, they find refuge in the houses of two local women, Maria and Amelita. They also realize that Tuscarora has been imprisoned by Hendricks for some trumped up charge. After an eventful meeting with the cranky, old Philips, the threesome- Cord, Cordona and Philips- sneak into Ketcham’s ranch, subdue him and his men , and force Ketchum to sign back the deeds to other ranchers. Cord also realizes that Ketcham is really Union Sergeant Major Ike Gorman, the second traitor\informer that he was searching for. After sending Cordona to fetch the American Cavalry, Cord and his group return to Rio Lobo, only to find the two women – who had sheltered them – viciously beaten by Hendricks- with Amelita’s face being disfigured with a knife. Cord’s gang, using Ketcham as hostage, forces Hendricks and his deputies to move out of the jail. Then Cord’s gang, now joined by Tuscarora as well, holes up in the jail and wait for the cavalry to arrive. But Cordon’s trip to fetch the cavalry is cut short by Hedrick’s men, who hold him hostage and demands the release of Ketcham. During the prisoner exchange, Cordona manages to give his captors the slip. Cord tells Hendricks that Ketcham is no longer of any use, since he signed back the deeds. Hendricks guns his boss down in rage, starting a firefight in which he and Cord are wounded. Amelita gets here revenge when shoots and kills Hendricks. The film ends with a crippled Cord, and a disfigured Amelita walking off together- reminiscent of the maimed comradeship of Duke and Robert Mitchum from the final scene in “El Dorado.”

Though Hawks is today considered a predominantly ‘Western’ film genre director, the fact is that he has made just five Westerns out of the Forty odd movies he had made in his career, with his first Western, “Red River,” starring Duke and Monty Clift, releasing as late as 1948- when he was already in his third decade as a filmmaker. The perception is because three out of his last five movies were Westerns, and even the fourth, “Hatari(1961),” was designed on the lines of Western, this time set in Africa. Since “Rio Lobo” is using the same formula third time around, it goes without saying that it’s not as good as its two predecessors- “Rio Bravo” and “El Dorado.” But we would not know that from the film’s first half hour, which is very inventive, and some of the best filmmaking Hawks has done in his career. The opening train hijack scene is a truly exciting actions sequence, and perhaps the most elaborate and spectacular action scene Hawks has ever directed- not discounting the cattle stampede sequence from “Red River.” Hawks was injured during the filming of the scene, and the sequence was mainly filmed by legendary stunt coordinator Yakima Canutt (of the Ben-Hur chariot race fame). The scenes involving the capture of Col. Cord is also very well done, how his troops are spread thin, and he’s left alone. The civil war era setting is also fresh for Hawks , and differentiates it from “Rio Bravo” and “El Dorado”; though not that fresh for Duke, who was just coming off “The Undefeated,” which was set in the same time period, and had Duke essaying a similar character of a Union officer turned civilian. Another great moment of the film is when Cord & gang enters the town of Rio Lobo for the first time; Hawks sets up an eerie mood by shooting the sequence in the darkness of night, in which the desert town looks like a ghost town, and there’s considerable suspense when Cordona steps out to leave the horses in the stables and he’s followed by Sheriff’s deputies. Another thing to note is that the film gets into “Bravo” territory only about two thirds into the narrative. Till then, most of the scenarios are fresh reworking of the said formula, though there are not new for a standard Western. But still, for a film that’s routinely referred to as one of Hawks’ and Duke’s worst – Quentin Tarantino particularly mentioned this film as the reason why he doesn’t want to have a long career- and considered nothing more than a lazy rehash of Hawks’ previous two Westerns, it’s pretty good, engaging, fresh and fun.

Where Hawks goes terribly wrong is in the casting. By Hawks’ on theory, if you could get a good enough actor opposite Duke then you will always end up with a good picture. In “Bravo,” there was Dean Martin, Walter Brennan, Ward Bond and Angie Dickinson; in “Dorado” he had Robert Mitchum, James Caan and Arthur Arthur Hunnicutt, but here, Hawks has populated the film with some of the worst supporting actors ever to appear in a John Wayne Western. Except for Jack Elam, who appears only by the final act, and who’s here in top form as a combination of Martin and Brennan from “Bravo,” the rest of them can’t even gets their lips properly around Hawks’ clever prose. Mexican heartthrob Rivero barely speaks English and he learned and delivered his lines phonetically, which is well reflected in his subpar performance and unintelligible line readings; imagine, Howard Hawks films are driven by meticulously constructed scenes of long, snappy conversations, and they couldn’t get an English speaking actor for the part, phew!. Bob Mitchum’s son, Chris, is also pretty ordinary, and miscast in the part; these two main supporting actors all but disappears in front of Duke’s screen charisma. But it’s the women who fares the worst, especially since Hawks has the reputation of being a great mentor to budding actresses (remember Lauren Bacall). This film has three ‘Hawksian’ women characters, but none of them are a patch on the angelic Angie Dickinson. One of them, Amelita, is played by future film producer and CEO of Paramount Pictures, Sherry Lansing, who did herself and the audiences a lot of good by switching professions. She can at least lay claim to being in the final shot of the final scene of Hawks’ final film, where she’s seen physically supporting none other than Duke Wayne. Jennifer O’Neill, whom Hawks had discovered for this film, turned out to be so bad – and clashed regularly with Hawks on set – that she was cut entirely out of the final thirty minutes of the film.

Hawks has tried to include more ‘Women’s issues’ into the script- women here don’t just wisecrack, and take the initiative in amorous encounters with men, but we see them beaten and bruised- physically and emotionally scared for life. I think both Hawks and Brackett wanted to delve deeply into the psyche of women, rather than projecting a certain female archetype. Though the film is mainly about Cord’s hunt for the traitors, it’s also driven by the stories of the women involved; and it’s Amelita to gets to kill the main bad guy. But these embellishments just don’t register: due to the ineffectiveness of the actresses, how badly they are directed, and how these issues are not developed beyond the surface level. The film is also edgier in the treatment of violence, we see the bullet holes and blood spurting out. The whole film has a more gritty and realistic look. William H. Clothier, who usually photographs his Westerns in vibrant colors, has gone for a more subdued color scheme, with some sequences looking as rough as Spaghetti Westerns. Jerry Goldsmith contributes an effective score for the film, even though the title music and the title sequence feels rather off: titles play out against the sounds and images of some dude playing the guitar; it’s very lazy and unimaginative. Additionally, there are script problems and direction problems that bogs the film down; by the time it enters the third act, everything starts feeling very familiar and tired. I bet that Hawks himself was bored by the end and just went through the motions. The final portions of the film play out like episodes from some cheap Western TV series. The climax is taken directly from “Rio Bravo”; even the location, sets and the stunts (involving prisoner exchange & use of dynamite) are the same.

But still, what makes this film an enjoyable watch is that Hawks is one of those directors who knows how well to use Duke- what really separate these first generation directors like Hawks, John Ford, Raoul Walsh, Henry Hathaway etc. from the next generation of filmmakers like Burt Kennedy and Andrew V. McLaglen is that that formers knew how well to use a star (especially John Wayne), and his specific talents to the betterment of the film and the star concerned. This is something the latter generation of directors never quite understood. A lot of the films made by Duke late in his career gave him roles that did not do justice to his talents and iconography, but “Rio Lobo” definitely uses both to its full advantage. The characterization, the dialogues, the behavioral patterns and character interactions that Hawks has designed for Duke is perfect for him. It’s in Hawks films, more than any other, where we seem to relish and appreciate the very easygoing, relaxed nature of Duke’s acting and his leisurely line readings; because generally (Westerns and more so) Duke’s Westerns are made up of ‘rituals’- rituals involving: meeting of friends, parting of friends, rejoining with friends, enemies turning friends; confronting, talking down, and shooting down enemies etc. – and in Hawks’ films everything take on the form of elaborate set pieces in itself. There are no elaborate mating rituals as in “Rio Bravo,” and that’s a big drawback of this film; by this time Duke was too old to be the traditional romantic lead, and he had stopped having romantic liaisons in his films.

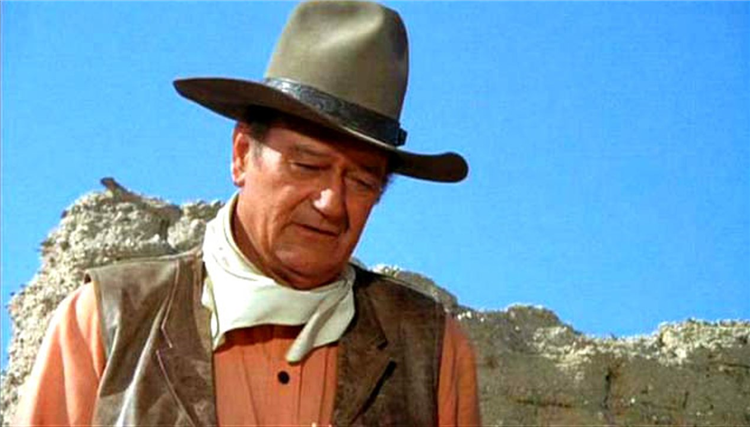

But there are other pleasures: just take the first meeting between Duke and Jack Elam, how they trade barbs, and how they move around in the screen; it’s almost like a dance. Duke singlehandedly (with some late help from Elam) drives this film from its beginning to its end, and makes sure that we audiences are with him all the way through, despite the several stumbling blocks on the way. Duke is not doing anything new nor is he even putting a new spin on the old stuff, he’s actually repeating a lot of the same stuff; and even in same scenarios (and even in the same clothes, same sets and riding the same horse). Also, Duke of “Lobo” is not the Duke of “Bravo” or “Dorado”; he’s far more plump and out of shape, less athletic and less energetic; the twinkle in his eyes has mellowed to become more melancholic; he has trouble getting on and off a horse; and by then he had even survived cancer, and lost a lung and few ribs in the process. But it’s a mark of what a great screen performer and Icon that he is that he still manages to hold the screen like no other; even in a film that’s not up to his mark. Only he can make a tired-old, traditional Western like this as tasty as comfort food- Duke’s referred to as ‘comfortable’ by one of the ladies in the film and that’s a term we can use to describe this film as well: familiar, and maybe even not very good, but nevertheless very enjoyable. Ultimately, that’s the takeaway from the great American director Howard Hawks’ final film: that he managed to make a very ‘comfortable’ John Wayne Western as his swansong.