True Grit is a story of a tough-talking teenage girl seeking revenge for the slaying of her beloved father. She hires the old, drunken US Marshal Rooster Cogburn to help her. By the time the film came out in 1969, the American Western as a genre had already run its course. These True Grit behind-the-scenes stories depict how both the original Henry Hathaway adaptation and the Coen Brothers’ 2010 installment went about breaking the rules to become the perfect revisionist model of the classic Western.

True Grit changes the rules of the genre. There are no classic Western protagonists; there is no higher moral ground where heroes wear white cowboy hats and villains are draped in black. John Wayne was the quintessential American movie Western protagonist. When he took on the role of the cantankerous, morally questionable Cogburn, the juxtaposition of persona helped to earn the Duke his only Academy Award. How dare Joel and Ethan Coen seek to remake such a movie classic, right?

But the Coens never questioned their motives; after all, they live in revisionist movie territory. The filmmaking pair have almost never made a straightforward genre picture. They routinely subvert genre convention while still managing to stay within the model’s malleable walls. In this case, the Coens opted to completely ignore the 1969 film. Instead, they used the classic Charles Portis novel as their only source material. From there, in trying to find the right actor for the story’s uncommonly complex heroine, the Coens landed on then-unknown Hailee Steinfeld among a sea of 15,000 contenders. And, of course, they convinced Jeff Bridges to take the role made famous by Wayne – and allowed him to wear the eye patch on the “wrong” eye.

Check out all the behind-the-scenes tales of both the original True Grit and its 2010 remake, all in one tidy list.

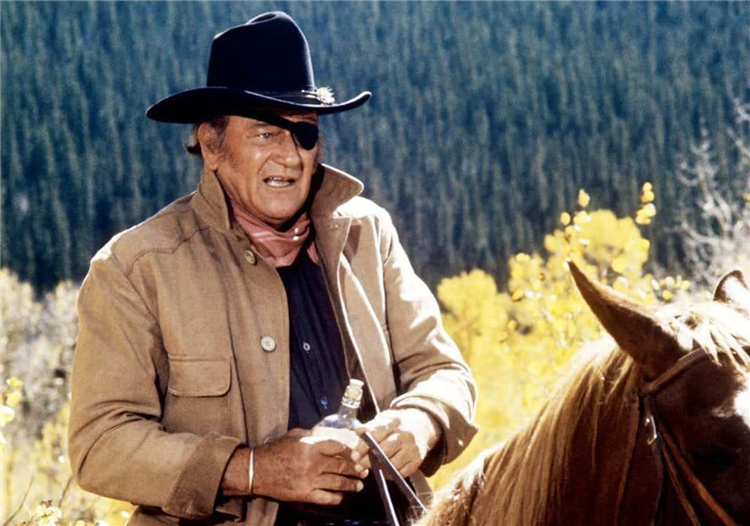

Jeff Bridges Did His Own Horse Riding – Two Arms In Hand, Reins In His Teeth – In The Film’s Climax

Jeff Bridges is willing to commit to a movie role, even if that means putting his life at risk. The climax of both True Grit movies involves Rooster Cogburn riding his horse without the use of his hands because he needs both guns to save the day. John Wayne may have won his only Oscar for his portrayal of the US marshal, but in filming the scene’s heroic ending, Wayne rode a moving truck instead of a horse. Of course, one can’t quite blame the late Hollywood legend, who was already in his 60s when he filmed True Grit.

Though Bridges was also in his 60s when he took over the role, he chose to take the true way and do the scene on an actual horse. Joel Coen revealed:

That was something we – and even Jeff – assumed would have to be fudged in one way or another, but he actually did all that for real. It was really quite difficult, manipulating those two big heavy [arms] with the reins in his teeth without being able to control the horse except with his legs.

Wayne Insisted On Being Able To See Out Of His Eye Patch

Rooster’s most defining physical feature is the eye patch over his left eye. The construction of a traditional eye patch would not typically present a veteran wardrobe designer like Luster Bayless too much trouble. However, the Duke wanted to actually be able to see out of the eye patch. He also requested that he get a fresh eye patch every day because they would get dirty.

Through trial and error, Bayless was able to construct an eye patch that Wayne could see out of by using gauze and window-screen mesh.

Hailee Steinfeld Beat Out 15,000 Girls In An Open Audition For The Lead Role

The Coen Brothers ran into a lot of trouble trying to cast the role of the 14-year-old, revenge-seeking, tough-talking, irrationally confident Mattie Ross. They auditioned over 15,000 actors online for the part originally played by Kim Darby. It’s a tough role for a young teen girl, and they could not find an actor who could handle the no-nonsense, quick dialogue. According to Joel:

Ninety percent of the kids just get eliminated for one very obvious reason: They’re not actors in any sort of natural way. Beyond that, the screenplay, as a reflection of the novel, is written in a very particular kind of language, so it’s almost like casting a verse player.

Just weeks before the film was set to start production, the Coens discovered an unknown 13-year-old actor named Hailee Steinfeld. The young starlet ended up clicking with Bridges and beat out her competition.

“Just the thought of it was kind of intimidating,” Steinfeld said of her audition. “But the minute I met [Bridges], I realized that he was just there to do a job – and I’m there for the same reason, and I kind of clicked with him and the Coen Brothers.”

All Steinfeld did in her first major big-screen role was earn an Oscar nomination for best supporting actress. Matt Damon could not believe the adjustments the still-green thespian could make after getting notes from the legendary directing duo.

“I saw the notes they were giving her, and they were some pretty complex adjustments,” Damon said. “And we’d do the scene again, and she’d just nail it. I remember looking up at [cinematographer] Roger Deakins and saying: ‘Is she doing this stuff every day? Is she that good?’ And he just nodded to me and said, ‘She’s that good.'”

The Coens Intended To Reunite With Bridges For Years After ‘Lebowski,’ But Hadn’t Found The Right Movie

The Coen Brothers clearly have an eye for casting. Perhaps their biggest home run was giving the part of Jeffrey Lebowski, AKA The Dude, to Bridges for their 1998 surreal comedy The Big Lebowski. It’s almost impossible to think of any other actor in the role. Bridges just is The Dude.

The Coens and Bridges knew that they wanted to work together again at some point. The filmmakers told the actor they were interested in making a Western. The idea intrigued Bridges… until hearing they were looking to remake True Grit with Bridges himself in Wayne’s iconic role of Rooster. Bridges’s first reaction was to second guess the Coens. He didn’t abide the idea of taking on the role that earned the Duke an Academy Award.

The Coens convinced Bridges to accept the role by insisting their version was not necessarily a “remake” of the original film. Instead, their source material was simply the 1968 Charles Portis novel, not the 1969 adaptation. Bridges said:

As soon as I read it, I saw what they were talking about because the book is wonderful, and it reads like a Coen Brothers script. So I took those guys up on that and didn’t refer to John Wayne or that other movie at all and just looked at the book. Took it totally fresh like I would any other part.

Before The First Night Of Shooting The Remake, Weather Covered The Set And Equipment In Two Feet Of Snow

The novel True Grit is primarily set in Arkansas, Utah, and Oklahoma. The 1969 adaptation opted to shoot in the Sierra Nevada and the Colorado Rockies. The Coens hoped to film in the same locales as the novel. They also wanted the movie to take place in the winter, but production did not start until the spring. The Coens settled on Texas for most of the interior shots and snowy New Mexico for the exterior shots.

The difficulty with shooting in a snowy area is that the weather can quickly get out of control. “It was blizzarding snow from the moment we came to New Mexico through the day we left,” Joel said. “The problem is that it’ll snow two feet – and 12 hours later, the snow will be going. So if you’re shooting a scene that takes a number of days, there’s no way to establish continuity. We ended up just moving around a lot.”

The first day of shooting proved to be one of the most difficult. After a major snowstorm in New Mexico, the crew’s equipment got covered under two feet of snow. They were forced to dig out the heavy equipment and move the entire set 150 miles away.

The production also had to deal with the extreme heat of Texas – though, for Bridges’s part, he said the weather helped him prepare to get into character. “It was tough, but not so tough that it shut us down completely,” he said. “It added a great deal of grittiness and reality to the whole thing.”

The Coens Only Focused On The Novel, And Didn’t Bother Watching The Original Movie

Mattie is the narrator in the Coen Brothers’ version of True Grit. Her perspective is similar to the book, which is told in the first person. The original actually featured Wayne’s character Rooster as the more central figure. The Coens’ take seems to make more sense. True Grit is, in fact, Mattie’s story to tell. It was her father who was executed by Tom Chaney, and it is she who sets out to seek revenge. The 1969 version most likely made the narrative shift because they wanted to highlight Wayne as the star of the movie.

Joel and Ethan Coen were so intent on just using the book as their film’s source material that they did not even revisit the 1969 original movie. “We saw it when we were kids; I don’t remember it at all,” Ethan revealed. “I assume they Hollywood-ized it.”

“I remember a couple points in production, actually saying, ‘You know, I should rent the movie and see it.’ And I just never got around to it. It’s really funny. It sounds unbelievable, but I just didn’t get around to it,” said Joel.

In fact, the only changes the Coens made to Portis’s 240-page novel were simply a result of not being able to fit everything into a two-hour movie. “Most of our changes are just omissions,” Ethan said. “Even that book, as short as it is, has a lot that you won’t find in the movie.”

Elvis Presley Was Originally Cast As La Boeuf, But Wanted His Name Above Wayne’s On The Marquee

By 1969, Elvis Presley had appeared in dozens of films. The King of Rock ‘n’ Roll could actually act. True Grit producer Hal B. Wallis was especially impressed with Presley’s performance in the 1960 Civil War-era Western Flaming Star.

Wallis gave Presley the part of La Boeuf. However, Presley’s agent wanted his client to have top billing – even over Wayne. That was a deal breaker for the production. Glen Campbell replaced Presley for the key role of the Texas Ranger. It was the country singer’s first feature film part. Campbell earned a Golden Globe nomination (most promising newcomer – male) for his debut performance.

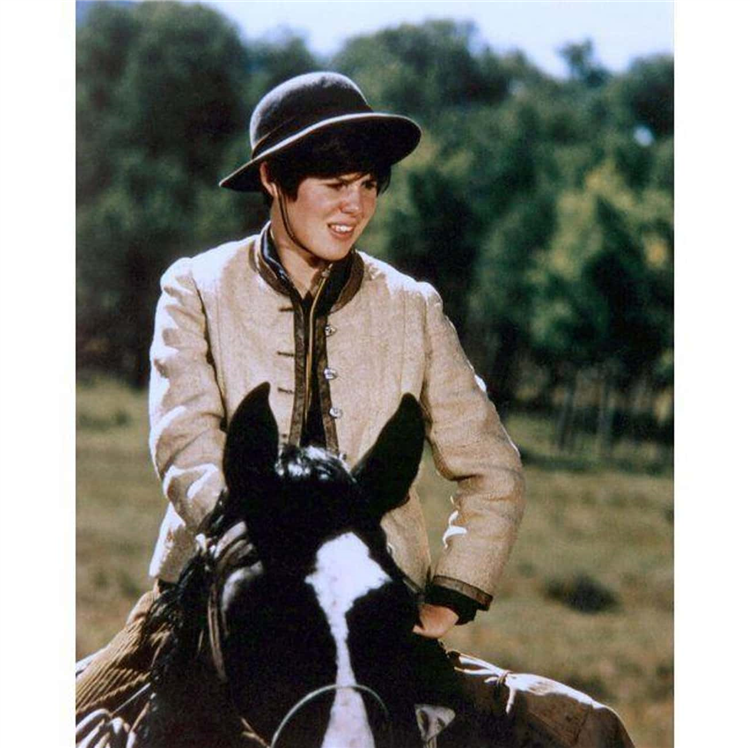

Darby’s Horse Riding Was Done By A 65-Year-Old Stunt Double Who Wore A Mask Of Darby’s Face

Kim Darby, who played Mattie in the original True Grit, was moved by young Steinfeld’s performance in the 2010 remake. It was the teen actor’s ability to ride a horse that impressed Darby the most. Darby claimed to only be on an actual horse for about five minutes of the 1969 film.

Not only was Darby not skilled at horseback riding, she was scared to even get on a horse. Thanks to the power of movie magic, Darby’s equinophobia was not an issue.

“I am really afraid of horses,” Darby said. “I had a stunt double. She was about 65. They made a mask of my face out of clay and she would wear that and it would match my profile.”

Robert Duvall And Darby Were Turned Off By Henry Hathaway’s Yelling And Impatience

By the time Henry Hathaway took the reins for True Grit, he already had over 60 directing credits on his resume. He also had a reputation for yelling at his cast and crew. The director explained the reason why he often screamed during production in simple terms: “To be a good director, you’ve got to be a b*stard. I’m a b*stard and I know it.”

Hathaway’s temper, however, was something 21-year-old Darby did not appreciate. Her first day of filming True Grit for Hathaway did not go well. “He was an old prop man and he usually focused on the prop man and he would just yell at him no matter what he did,” Darby said. “It got me so off guard. I just got up and went back to my dressing room.”

Afterward, Darby and Hathaway were able to talk it out. The actor told the director she would follow his direction but asked that he not yell at her. “After that day, we went along swimmingly,” said Darby.

Newcomer Campbell, who played La Boeuf, also took umbrage with being yelled at by Hathaway, and even confronted the director: “You know, I can get on a horse and get out of here and get in my car and go back to LA. He kind of looked at me and said, ‘Well, I have been tough on you.’ That was Henry Hathaway.”

Legendary actor Robert Duvall, who played Ned Pepper in the 1969 Western classic, clearly held residual disdain from working with Hathaway: “John Wayne, he was a wonderful man. But Henry Hathaway – we won’t talk about him.”

The Original Producer Bought Copies Of The Novel In Bulk To Make Sure It Was A Bestseller

What does it take to get a book to become a New York Times bestseller? One old-school method was to find a way to fudge the numbers.

Bob Rehme served as a publicity executive on True Grit. It was his job to make sure the Western coming-of-age saga became a hit movie for the studio. Rehme concocted a plan for Paramount staffers to purchase entire boxes of the Portis novel from different bookstores. The numbers from these sales were kept by The New York Times for their bestseller list. Rehme then sent the books out to the media in order to further promote the novel and upcoming screen adaptation.

And it worked! When True Grit began production, the source novel already hit the No. 2 spot on the NYT list. Today, a clever plan like Rehme’s wouldn’t work out so well. The NYT bestseller list uses a dagger symbol to identify these kinds of large sales.

Still, Rehme’s clever plan doesn’t take away from the accolades Portis’s debut novel earned. It is often cited as one of the great American novels and a must-read that can entertain nearly all ages. Acclaimed television writer (The Wire) and American author (The Night Gardener) George Pelecanos discussed the power of Mattie’s character:

Mattie’s voice, wry and sure, is one of the great creations of modern American fiction. I put it up there with Huck Finn’s, and that is not hyperbole. In fact, I find True Grit to be one of the very best American novels: It is a rousing adventure story and deeply perceptive about the makeup of the American character.

Wayne Thought Marguerite Roberts’s Script Was The Best He Had Ever Read

Wayne read Portis’s 1968 novel True Grit and became so enamored with it that he had his company, Batjac Productions, bid to acquire the film rights. Producer Wallis outbid Wayne – but he only secured the rights to have a starring vehicle for the Duke.

On paper, it may have seemed odd for Wayne to star in a Western in which his character is a drunken, overweight, ornery US marshal. When old movie audiences think of Wayne, they envision a wholesome (if prickly) hero with a high moral standard. Yet, the juxtaposition obviously worked. The Duke won his only acting Oscar for his portrayal of Rooster.

Wallis hired veteran screenwriter Marguerite Roberts to write the screenplay. It was a natural fit for the production. “Daddy put me on a horse before I knew how to walk,” said Roberts. “I was weaned on stories about gunfighters and their doings, and I know all the lingo, too.”

Roberts often used the book’s dialogue word-for-word in her script. For example, Ned Pepper said verbatim in both the book and film: “I call that bold talk for a one-eyed fat man!”

Additionally, Rooster said in both versions: “Fill your hand, you son of a b*tch!”

The writer’s past political activism became a worry. In the 1930s, Roberts was one of the most prolific and financially successful screenwriters in Hollywood. Then, she became affiliated with the Communist Party and was forced to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Like many screenwriters of the day, Roberts refused to name names. The writer was subsequently blacklisted for an entire decade from 1952 to 1962.

Wayne was a well-known conservative who supported HUAC, and there was initial worry that Wayne would refuse to read Roberts’s script. In the end, the Duke didn’t just read it – he called it the best screenplay he had ever read.

The Coens’ Remake Wasn’t Seen Or Even Completed Until A Few Weeks Before Release

The Coen Brothers often make films that attract award nominations. Prior to 2010’s True Grit, the Coens had already won four Oscars – twice for writing, once for directing, and once for the top prize of best picture. Titles like Fargo; No Country for Old Men; O Brother, Where Art Thou?; and A Serious Man have all racked up both Academy Award nominations and wins.

Paramount Pictures figured the Coens’ 2010 revisionist Western would also be a hit with the Academy. The studio asked the filmmaking duo to have True Grit ready by the holiday season, which coincides with the time of year many Oscar contenders are typically released. Weeks prior to the film’s release date, no one had actually seen True Grit. Speculation grew that there were problems with the production. However, according to Joel, that was not the case – and in fact the explanation was much simpler:

They decided before we started shooting the movie, they said, “We’d like you to get this ready in time for Christmas, can you do that?” We went, “Er, okay. That’s very short, but we think we can.” And then it was a big crunch to get it through. But it is interesting, in the press they go, “They’ve been withholding this.” I’m going, “The movie didn’t exist!”

Mia Farrow Called Her Departure From ‘True Grit’ The Worst Career Decision She Ever Made

Mia Farrow was just starting her movie career in the late 1960s. The actor was coming off her first big-screen starring role as the tragic eponymous character in Roman Polanski’s horror classic Rosemary’s Baby. She signed on to play Mattie in True Grit, but was then talked out of the role by Robert Mitchum. Farrow and Mitchum worked together on the film Secret Ceremony in 1968. Mitchum, who worked with Hathaway on the 1968 Western 5 Card Stud,urged Farrow against working with the cantankerous director.

The actor reportedly spoke with producer Wallis and asked him to fire Hathaway and replace him with Polanski. Wallis wouldn’t go along with her request, and Farrow left the production. It was a decision the actor would later regret, even calling it “the worst career choice I ever made.”

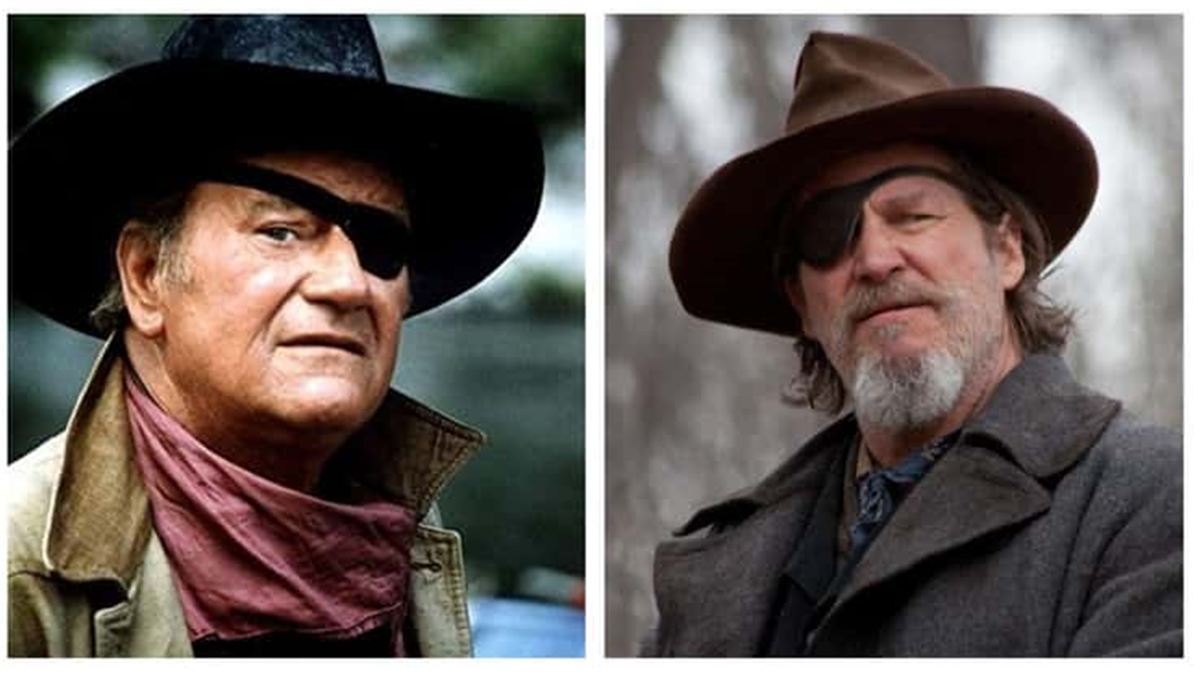

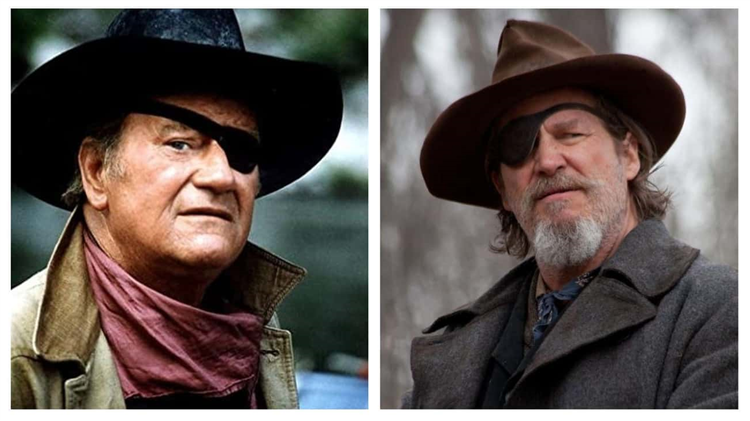

The Coen Brothers Joked About Switching Rooster’s Eye Patch For Every Scene

Astute movie viewers will notice that Wayne wore Rooster’s iconic eye patch over his left eye (like in Portis’s novel), while Bridges wore the patch over his right eye. What was the reason Bridges and the Coen Brothers decided not to follow precedent? Turns out it was simply a matter of comfort, according to Bridges:

Uh, you know, we put it on the right eye and it felt good. We put it on the left eye, uh, not so good. Put it on the right eye, uh, “This feels right.” And then we went back and forth like that.

The Coens even thought about using the eye patch to have a little fun with the audience. As Ethan described, “We did talk about switching from eye to eye, scene to scene to see if anybody would notice.”