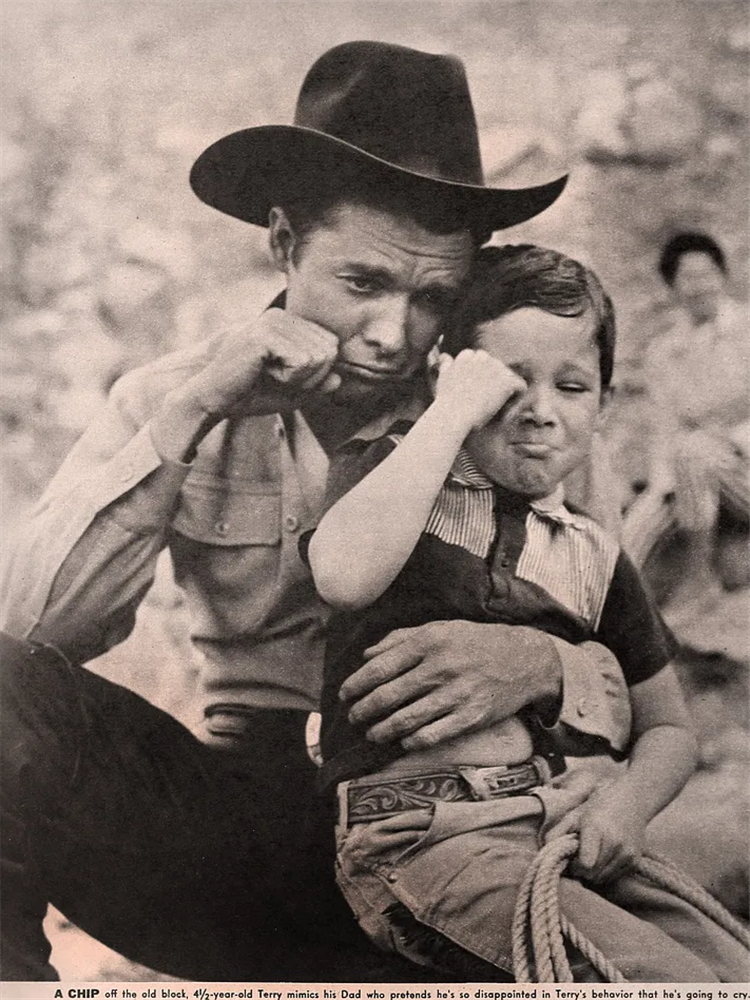

“Audie Murphy read the Dirty Harry script and told eldest son Terry that he couldn’t do it as the role of Scorpio would have blown his image wide open.” So goes Robert Nott’s 2015 tome Last of the Cowboy Heroes: The Westerns of Randolph Scott, Joel McCrea, and Audie Murphy.

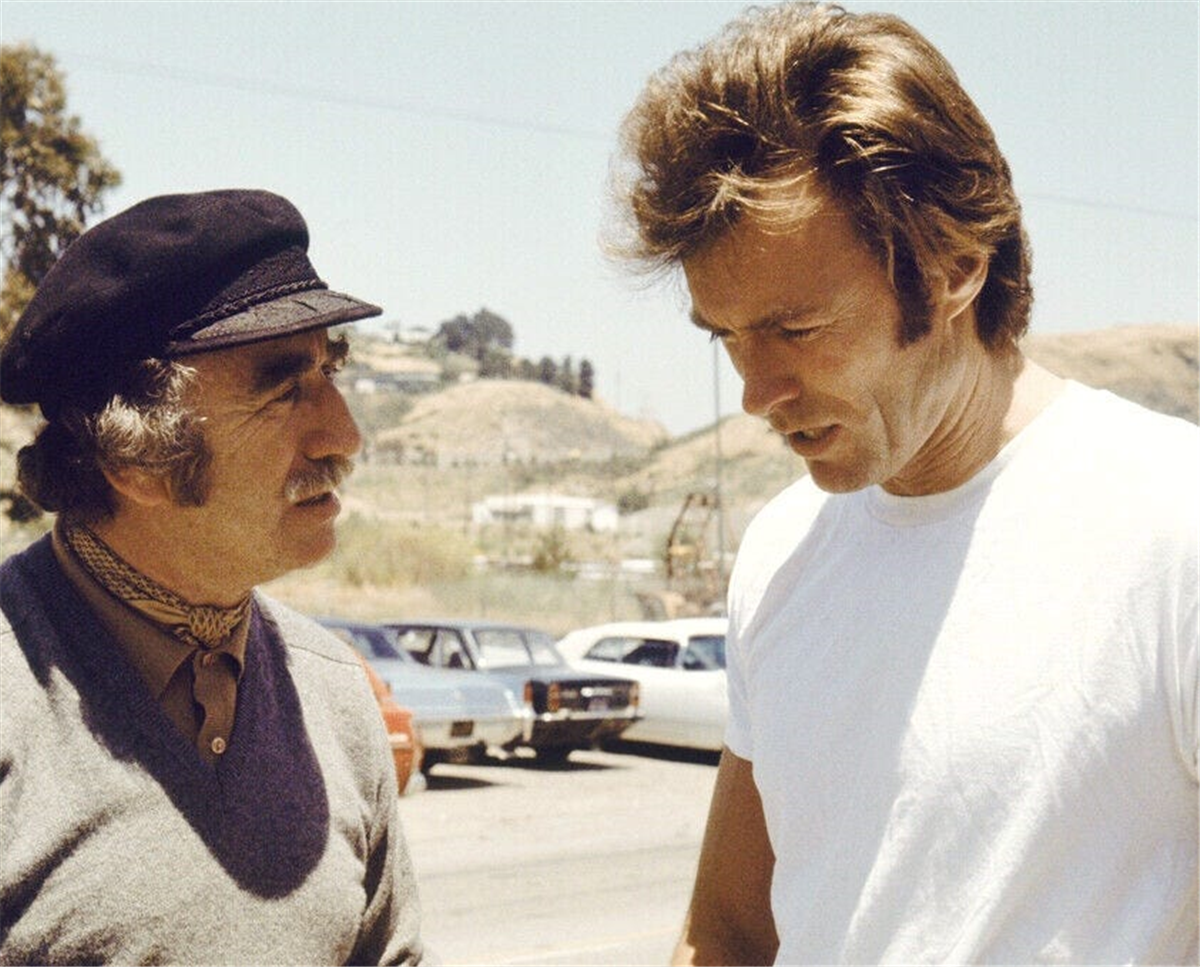

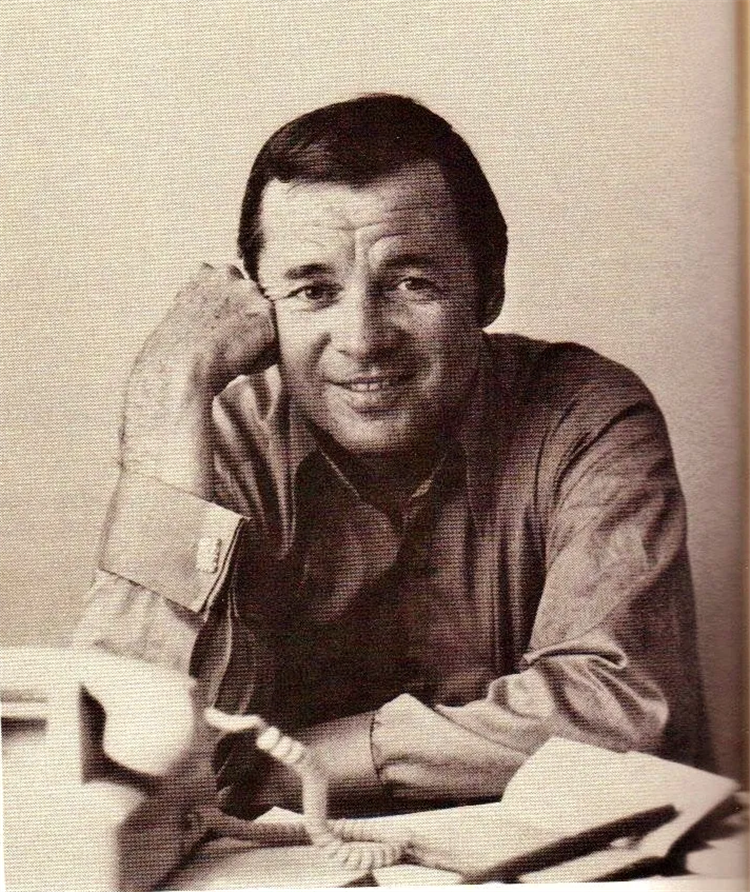

However, in a first-hand account much closer to the event in question, Dirty Harry director Don Siegel sat down with Stuart M. Kaminsky for a 1974 biography as sourced in Don Graham’s No Name on the Bullet: A Biography of Audie Murphy. “I hadn’t seen Audie for awhile, and I met him on a plane on the way back from the Dallas Film Festival where I had been with The Beguiled,” recalled Siegel [the chambered psychodrama starred Clint Eastwood as a manipulative Yankee soldier recuperated by a band of lonely school girls and opened the festival on March 8, 1971].

Siegel elaborated, “Audie seemed genuinely happy to see me, as I was to see him. Audie didn’t want to bother me because he could see I was reading a script. I told him to sit down. We started to talk and I suddenly realized, ‘My God, I’m looking for a killer who could be lost in a crowd, a man who wears suits, a man who might sell you insurance. And here’s the killer of all time — a World War II hero who had killed over 250 Germans.’

“It would have been the easiest part of Audie’s life. Warner Bros. executives weren’t convinced that Audie could handle the acting and rejected my suggestion.” Reckon they hadn’t seen The Red Badge of Courage, To Hell and Back, Walk the Proud Land, No Name on the Bullet [Murphy as a mysterious killer-for-hire stalking his next victim], The Unforgiven [a hot-headed rancher incensed to learn that adopted sister Audrey Hepburn is a Native American], or Posse from Hell. Siegel offered Murphy 2% of the gross, which would have nabbed him a cool $600,000 check as Dirty Harry’s runaway box office receipts cemented Eastwood’s rogue cop persona. Murphy’s penchant for gambling and ill-advised investment schemes had left his finances in tatters.

In retrospect, Warner Bros.’ decision seems bone-headed, but in 1971 Murphy had not graced a marquee since 40 Guns to Apache Pass for Columbia. His fine cameo as gunslinger Jesse James in Budd Boetticher’s A Time for Dying was languishing in post-production financial difficulties and no distributor dared touch it. Four years of screen inactivity in the Swingin’ Sixties was an eternity. Warner Bros. was not beholden to Murphy, as his sole collaboration with the studio had been over a decade before in the Cuban Revolution-set film noir The Gun Runners, directed by — you guessed it — Don Siegel [the duo also teamed up for The Duel at Silver Creek, a 1952 Universal western boasting a strong supporting cast and plenty of six-gun score settling].

Siegel knew a thing or two about coaching tall-in-the-saddle cowboys to reach naturalistic performances. “Audie didn’t drink, was on time, and caused very little trouble as long as you didn’t tread on his temper,” the future director of The Shootist, John Wayne’s last western, keenly observed. “Audie was incredibly shy and strange. There was a problem reaching him to get a good performance in The Gun Runners. Something was bothering him. Audie carried a loaded gun and one time jumped across the boat at a member of the crew. I had to pull him off [Murphy was 5-foot-8.5 inches tall and 160 pounds]. Even the tough guys on the set, the stunt men, would take detours so they didn’t have to walk past him. But Audie was always polite to me.”

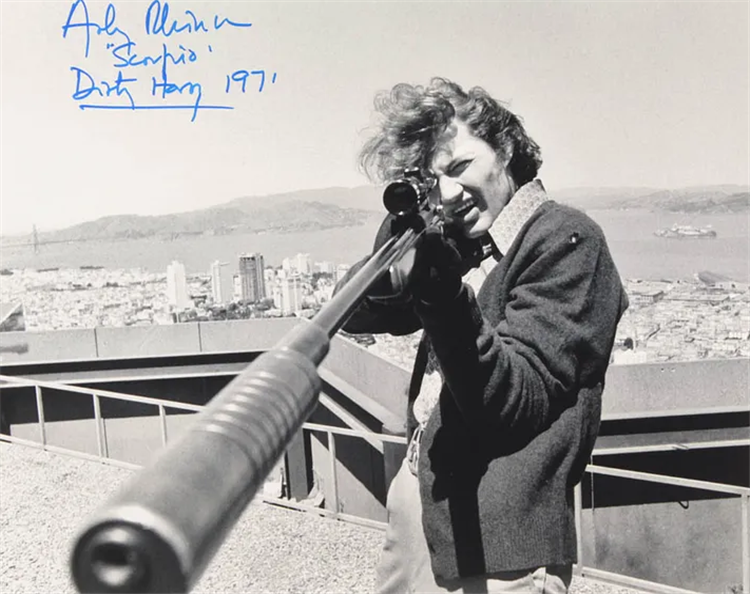

Siegel caught Andy Robinson starring in the off-Broadway play Subject to Fits at the New York Shakespeare Festival’s Public Theater [premiering on Valentine’s Day 1971, the play ran approximately a month]. Robinson effectively rendered Myshkin, a epileptic Russian prince based on Dostoevsky’s 19th century novel The Idiot transported to contemporary society. Siegel offered Rob inson the Scorpio part as he possessed “the face of a choir boy.”

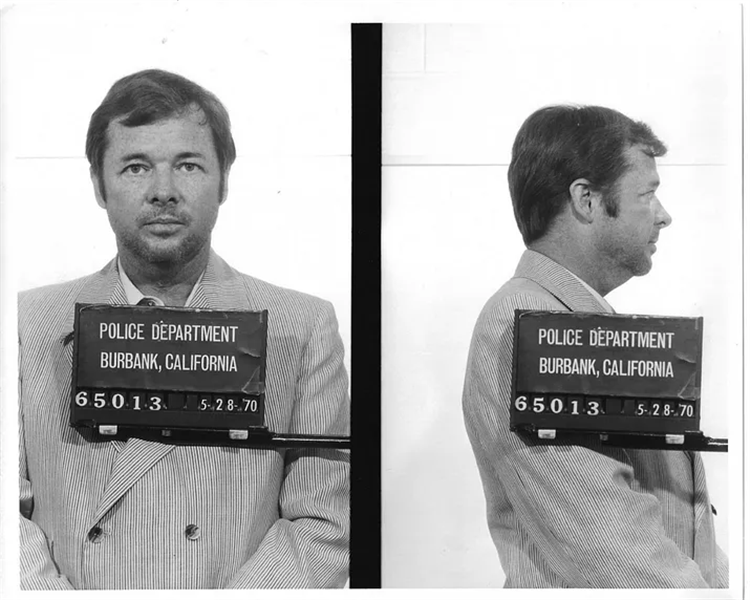

The AFI Catalog of Feature Films verifies that Dirty Harry was announced in November 1970. Shooting commenced on April 20, 1971, and wrapped by mid-June. Murphy was still alive until May 28, so his shocking death in a private plane bound for Martinsville, Virginia, was not the reason why the soft-spoken 45-year-old didn’t win a turn in Dirty Harry.

Sighting a high-powered rifle with a silencer, Andy Robinson is the disturbed “Scorpio” sniper of women and children in director Don Siegel’s uncompromising “Dirty Harry.” Note Robinson’s genuine autograph in blue ink. Image Credit: Pristine Auction

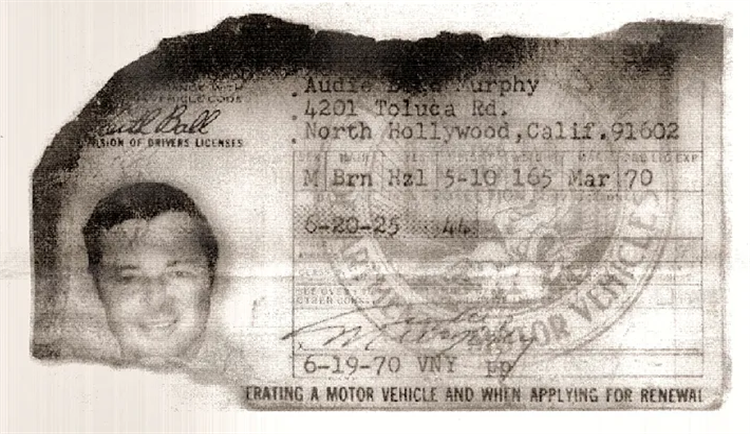

The charred driver’s license of Audie Murphy was discovered in the wreckage of the Colorado Aviation Aero Commander 680 that slammed into Brushy Mountain, Virginia, due to poor visibility over Memorial Day Weekend 1971. Murphy, four other passengers, and the pilot were all killed instantly. Image Credit: Audie Murphy Research Foundation

The charred driver’s license of Audie Murphy was discovered in the wreckage of the Colorado Aviation Aero Commander 680 that slammed into Brushy Mountain, Virginia, due to poor visibility over Memorial Day Weekend 1971. Murphy, four other passengers, and the pilot were all killed instantly. Image Credit: Audie Murphy Research Foundation