At the heart of “Gran Torino” is the portrayal of a good man. Too often good characters are simpering or squeaky clean; if not flawless their flaws are superficial traits plastered on top by a mediocre filmmaker. But Clint Eastwood’s Walt Kowalski comes across as authentic because of all the faults our society recognizes in the old white man.

Clint Eastwood made his name with a squint, a glare, a snarl, and a few well-chosen one-liners. His vigilante loner has served him well in films from the spaghetti Westerns, the Dirty Harry franchise, Unforgiven, Pale Rider, and more.

All these roles are summed up in Walt Kowalski—the main character in the 2008 film Gran Torino —a film Mr. Eastwood directed and a character he suggested would be his last acting role.

Kowalski is a cantankerous, retired Polish American car factory worker and Korean War veteran. Recently widowed, he’s seen his once-proud, working-class neighborhood of Detroit first abandoned and then taken over my poor Asian immigrants. Meanwhile, Walt’s children and grandchildren have moved out to the affluent suburbs to pursue a mindless consumerism.

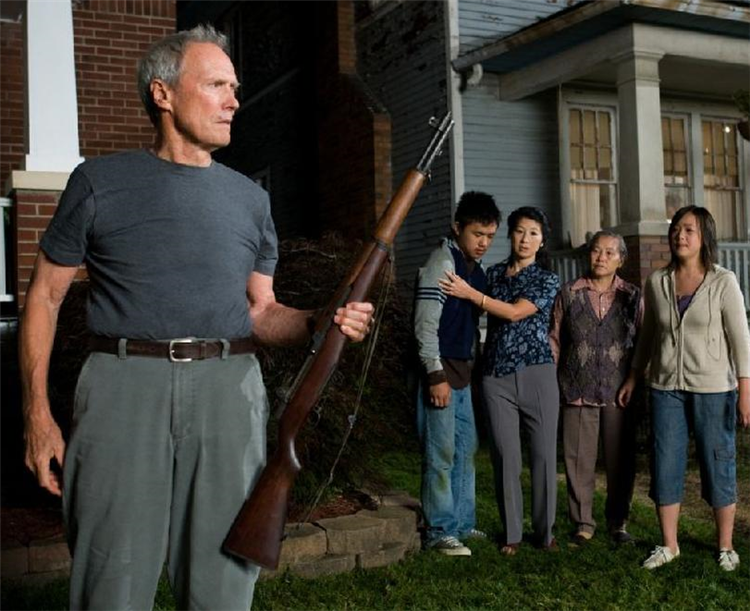

Determined to stay in his old house, Walt spurns his son and daughter-in-law’s suggestion of moving to an ersatz retirement home. The Asian gangs in the neighborhood bully the boy next door, encouraging him to steal Walt’s vintage Gran Torino car in an initiation trial. When Walt catches the boy, a grudging friendship between the two develops, and the lonely old man is eventually befriended by the Asian family. As the film rises to a climax, Walt and the gang members come to a typical violent stand-off with a sly twist.

Mr. Eastwood’s gun-toting characters echo through the film. Surveying the scene with his silent squint, Walt reminds us of Mr. Eastwood’s early tough days as rawhide cowboys. In his relationship with the Asian family next door we see the concerned but vengeful preacher of Pale Rider. When he confronts the gang members we can almost hear Harry Callahan snarl, “Do you feel lucky punk?” In Walt’s introspection, guilt ,and regret for his violence in the Korean War, we remember the guilt of retired gunslinger William Munny in Unforgiven.

Mr. Eastwood has often been criticized not only for the violence in his films, but for playing white male vigilantes driven by conservative values. In Gran Torino he takes the trope and expands it from the inside. Walt Kowalski, it turns out, is a lapsed Catholic. Impatient with the youthful parish priest, and grieving for his dead wife, he is also grieving for a lost way of life, and if the subtext be told, is also lamenting a Catholic faith that was lost in the ruins.

As such, the themes can be seen as socio-political. Walt could be the typical Trump voter. Grieving over a lost way of life, he’s angry, resentful, and alienated. His world h as been invaded, and he knows that everything he’s held dear is gone and everything he fought for was in vain. The film is now ten years old, so if this political angle is accurate it was prescient rather than planned. The human values and themes of the film are more important.

They play out as Kowalski warms up to the Asian families and overcomes his bigotry. While his bigotry isn’t excused, it is explained: He’s still carrying wounded memories from his time in combat in Korea, and even though the Asian neighbors are not Korean, he reacts with revulsion towards people who typify the old enemy. As the film gears up through the second act we also learn that Walt is suffering from emphysema and doesn’t have long to live. This prompts a heart-to-heart with the young priest and a visit to the confessional, which shows, beneath the surface, the curmudgeon is a genuinely humble person.

At the heart of Gran Torino is the portrayal of a good man. It’s a well-known problem that it is easier to create an interesting villain than an interesting hero. Too often good characters are simpering or squeaky clean; if not flawless their flaws are superficial traits plastered on top by a mediocre filmmaker. Clint Eastwood’s Walt Kowalski comes across as authentic because of all the faults our society recognizes in the old white man. Kowalski is racist. He’s grumpy. He’s been an inadequate father. He’s angry. He’s outnumbered, alienated, and alone. These are not superficial flaws, but ingrained character traits that seem to dominate Walt’s character.

When I was studying screenplay construction the teacher said, “Let your character grow from his wound.” Mr. Eastwood and the scriptwriter Nick Schenk do just that. They use Walt’s flaws not only to add verisimilitude, but also to provide the film’s turning point. We’re interested in the tension and conflict provided by the threat of the gang members, but we’re more interested in Walt’s loss, his grief, and loneliness. We want the gang members to be defeated, but we really want Walt’s bigotry and loneliness to be defeated.

Gran Torino works because, in the end, we not only sympathize with Walt, but we see that he is a genuinely good man. This is the film’s great strength and moment of enlightenment: If we were judging Walt for his bigotry and only looking on the outward appearance, we suddenly realize that we were also guilty. We were only looking on Walt’s outward appearance. We were Walt.

Gran Torino is a little film. The budget was small, the action was local, and Mr. Eastwood is the only star. The hero doesn’t save the world. Walt just learns to help his neighbor and find a way to find his faith and save his own soul, and in this troubled and confused age, that may be exactly the salvation we need.

This essay was first published here in December 2018.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.